Why did Sony buy Alamo Drafthouse — and is it actually a good thing?

Despite the historical importance of the Paramount decrees — which for decades governed the way movie studios did business with theaters — few people really understand them, including those who work in Tinseltown.

All this came up again last week when Sony Pictures announced that it had acquired Alamo Drafthouse Cinemas, the quirky Austin, Texas-based chain that operates 35 locations, including one in Los Angeles.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court made the consequential decision to break up the studio system’s old vertically integrated oligopoly, in which a handful of big companies not only controlled the production and distribution of movies but also had a huge hand in exhibition by owning theater chains.

The landmark antitrust case altered the structure and trajectory of the entertainment industry, marking a pivotal moment during Hollywood’s Golden Age. The result was a series of settlements between the companies and the government that forced studios to divest their theater assets and blocked other anti-competitive practices.

But while the decrees — which were lifted a few years ago — have long been popularly understood as a blanket prohibition on studios investing in theaters, the reality is more complicated.

As we wrote in 2018, when the Department of Justice opened its review of the settlements, the history here is long and complex.

After the decrees, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox and MGM were barred from reentering the theater business without court approval. However, others were not. Columbia, for example, didn’t own theaters at the time, so it wasn’t enjoined from acquiring them in the future. Paramount itself avoided some of the constraints placed on rivals by settling early.

In fact, Columbia and others have tested the waters for decades, with the taboo beginning to fade as early as the 1980s. In 1985, Columbia (now Sony Pictures) acquired the Walter Reade circuit in New York. Sony later owned the Loews theater chain, which is now part of AMC. Paramount and Warner Bros. co-owned Mann Theatres for many years.

So it’s not necessarily that these movie studios couldn’t own theaters. The question, given the state of the business, is: “Why would they want to?”

Box office in the U.S. and Canada is still down 24% so far this year compared with 2023, according to Comscore, notwithstanding the success of Pixar’s “Inside Out 2.” For theaters, staying in business means negotiating with landlords and creditors while waiting for blockbusters, which are few and far between now, partly because of studio cutbacks and strike-related production delays.

Anyway, back to Sony buying Alamo Drafthouse.

The craft beer-pouring Alamo is well known among cinephiles for its special-event screenings of old movies, its strict anti-texting policy enforcement and for helping to pioneer the now ubiquitous dine- and drink-in theater concept (its downtown L.A. spot is, incidentally, equally famous among attendees for its maddening parking situation). So the Sony acquisition has gotten a fair amount of attention, especially on Film Twitter.

Reactions in the movie theater business have been varied. Several operators contacted by The Times said they were surprised by the news and did not yet know what to make of it. Sony and Alamo did not make executives available to be interviewed for this story.

Content producers have dabbled in buying theaters in recent years, with Netflix acquiring the classic Egyptian Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard and the Bay Theater in Pacific Palisades. Those, however, were largely seen as exercises in branding and promotion and, in the case of the Egyptian, relationship-building with filmmakers.

So yes, this is the first time in a while that a major studio has bought an actual commercial chain. But it’s a relatively small one. If Disney or Universal were coming in to buy AMC, this might be a different story. And whatever competitive concerns owning a theater circuit might raise in effect have been rendered moot by the fact that most of the studios essentially control production and exhibition in another, more meaningful sense: by operating their own streaming services.

For Alamo and its fans, the deal serves as a lifeline. The company, like other theater owners, suffered badly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns and the slow subsequent box office recovery. Alamo filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2021 and emerged under the ownership of its private equity creditors, joined by its founder, Tim League.

On the studio side, the purchase appears to be another way for Sony and its leaders, including film group Chairman Tom Rothman, to demonstrate their commitment to theatrical distribution.

The company has supplied a number of hits to multiplexes lately, including “Anyone But You,” “The Garfield Movie” and “Bad Boys: Ride or Die.” Unlike its major competitors, Sony does not have an affiliated mass market streaming service, not counting its popular anime brand Crunchyroll.

B&B Theatres’ Brock Bagby said in an email that he’s happy to see a studio “double down” on theaters, though it’s unclear — and, in my view, unlikely — that this will lead to a broader trend of entertainment giants consolidating exhibition.

“We feel this solidifies what we have been telling our banks and landlords, that studios experimented with streaming and day-in date-titles but ultimately, we all make the most money showing movies exclusively in theaters first,” Bagby said. “Does this mean there will be other studios buying theater chains? No idea, but it’s exciting to see Sony stepping up in a big way to support theatrical first.”

If Sony is going to dive into the theater business, Alamo is as good an option as any. The company is one of the few film exhibitors that has built a distinct brand without meme-stock vibes and Nicole Kidman commercials.

Sony can also use its new theaters as an opportunity to create event-type experiences for its own releases and franchises throughout the company, taking advantage of the chain’s footholds in major markets, including New York, Boston, Chicago and San Francisco, as well as Los Angeles.

Lest we forget, Sony, in addition to its film properties, owns television staples such as “Jeopardy!” and “Wheel of Fortune,” which could lend themselves to the kind of in-person entertainment extensions Sony seems interested in pursuing. Sony will surely use the new platform to boost its Crunchyroll distribution engine, which has seen a string of box office successes.

Roth MKM analyst Eric Handler pointed out that Sony Pictures’ Tokyo-based parent company has loads of PlayStation video game intellectual property that it could use to eventually grow an in-theater esports business, just to float an example.

“I don’t think Sony has an endgame to be a sub-scale movie theater operator, and I don’t see them trying to swallow up a lot of theater chains,” Handler said in an interview. “But this is a company that wants to leverage its IP, and I think they want to do so through experiential types of endeavors.”

That’s the exact kind of thing Sony would need to tread lightly with if it wants to preserve the chain’s rebellious movie fan-first identity. Turning Alamo locations into big-screen PlayStation gaming parlors would certainly be one way to send the Letterboxd crowd into panic mode. That’s one major reason why I doubt the acquisition will lead to any drastic changes, especially right away.

Besides, there are far worse fates for a mid-tier theater chain than selling to a studio. Los Angeles’ Cinerama Dome and the adjacent former ArcLight theater on Sunset Boulevard remain closed, a stark reminder of the long-term damage done by the pandemic. As one veteran industry pro put it to me: “It’s money coming into the industry that’s not debt — it’s not vulture money.”

You’re reading the Wide Shot

Ryan Faughnder delivers the latest news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Stuff we wrote

‘Unprecedented time’: Hollywood slowdown brings peril for talent agencies, managers. As work in Hollywood has slowed down this year on U.S. series and movies, talent reps are adapting by taking on consulting jobs and marketing their clients overseas.

With Hollywood shedding jobs, here is help for coping with the slowdown. Workers in the entertainment industry are struggling. The Times has compiled a guide that offers tips on finances, mental health and accessing funds.

Why Shari Redstone went cold on a Paramount sale to Skydance. The mogul’s stunning eleventh-hour reversal came after a financial deal had been reached with David Ellison’s Skydance Media. For now, the storied media company will attempt to go it alone.

As streaming becomes more expensive, Tubi cashes in on the value of free. Subscription prices for Netflix, Disney+, Max and Peacock have crept up in the last year, and more consumers are turning to the free, ad-supported video-on-demand streaming service owned by Fox.

Elon Musk blasts Apple’s OpenAI deal over alleged privacy issues. Does he have a point? The Tesla and SpaceX leader’s beef with OpenAI flared up again after Apple unveiled its plans to use ChatGPT to support some of its artificial intelligence features. Apple said privacy is a key component of its entry into the space.

ICYMI:

Halyna Hutchins’ Ukrainian family sues Baldwin, ‘Rust’ producers

The Disney-DeSantis feud is officially over with $17-billion deal

Disneyland union files charges in Mickey button dispute

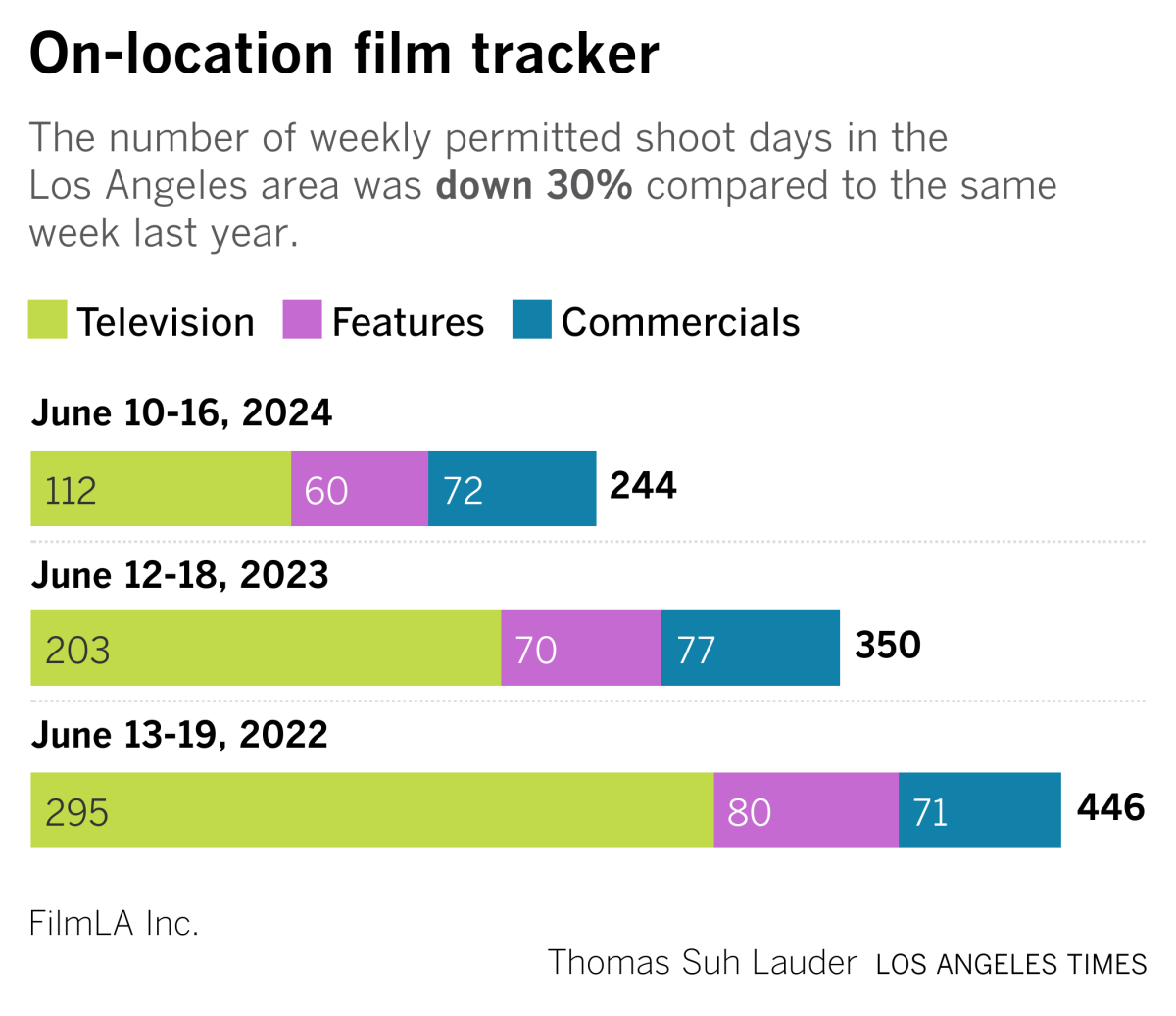

Film shoots

This week’s production chart shows that L.A. shoot days still lag far behind last year.

Finally ...

I attended Day 2 of the Hollywood Bowl Jazz Festival on Sunday (happy Father’s Day, fellow dads!) The highlight for me was singer Yebba, whose guest vocal performance during Robert Glasper’s set brought down the house.

The Wide Shot is going to Sundance!

We’re sending daily dispatches from Park City throughout the festival’s first weekend. Sign up here for all things Sundance, plus a regular diet of news, analysis and insights on the business of Hollywood, from streaming wars to production.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.