Rare magnitude 4.8 earthquake rattles New Jersey and New York, is felt across Northeast

A rare magnitude 4.8 earthquake rattled New Jersey on Friday, shaking buildings in Manhattan and sending tremors across the Northeast United States, a region unfamiliar with much seismic activity.

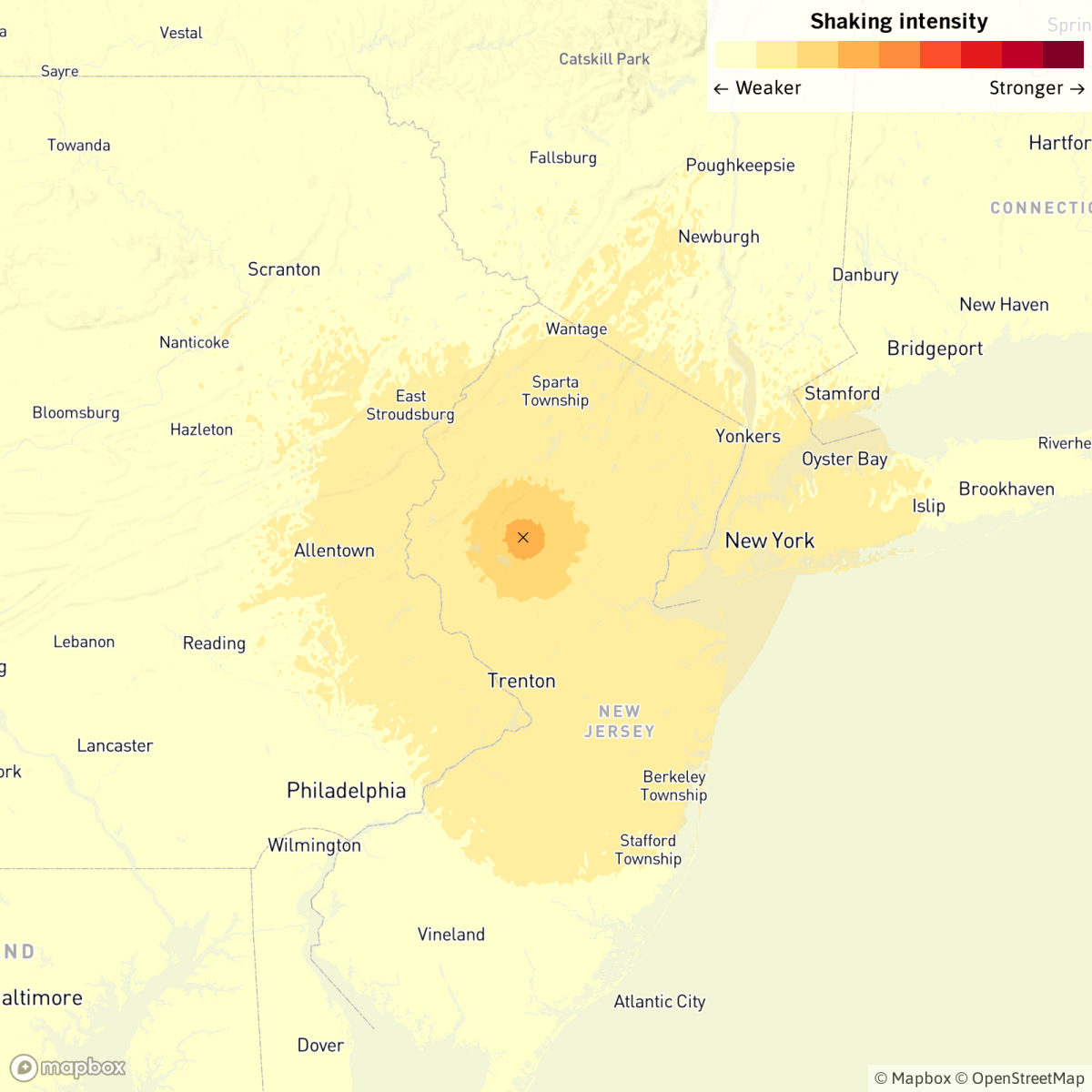

The U.S. Geological Survey said the quake was felt across New York, Connecticut and Pennsylvania. It struck about 40 miles southwest of Manhattan at 10:23 a.m. Eastern time. Its epicenter was less than 1 mile northwest of the unincorporated community of Oldwick, N.J.

Weak shaking was felt from Washington, D.C., to Maine, including in Boston, Philadelphia and Albany, N.Y.

There were no immediate reports of damage or injuries, but in New York City, people reported feeling buildings sway. Then, at 11:02 a.m., they received a beeping emergency alert on their phones urging them to stay indoors and call 911 if injured.

At busy intersections, people’s cellphones shrieked as a series of the same alerts warned of aftershocks.

In midtown Manhattan, convenience store proprietor Arun Kumar, 50, said he thought the rattling was a heavy truck passing nearby.

“But it felt a little weird, a little different, you know?” he said.

Maria Marta, 75, who was visiting from Buenos Aires, said she barely felt a tremor. But she lived in the city in the 1980s and experienced an earthquake then.

“It’s New York, you know?” she said Friday. “Anything can happen.”

The Federal Aviation Administration initially warned that the quake could disrupt air traffic facilities in New York, New Jersey, Philadelphia and Baltimore. Three hours after the quake, Newark Liberty International Airport’s “air train” service, which carries passengers between the airport train station and the terminals, remained suspended for inspections.

President Biden said Friday from the White House that he had spoken with New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy.

“He thinks everything is under control,” Biden said of Murphy. “He’s not too concerned.”

The guide to earthquake readiness and resilience that you’ll actually use.

The USGS said there was “a low likelihood of casualties and damage” from the quake.

According to the agency, strong shaking was felt at the epicenter, as defined by the Modified Mercalli Intensity Scale. That’s enough to be felt by everyone, but cause only slight damage.

A large part of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast felt weak shaking, according to people who filed reports to the USGS’ “Did You Feel It?” tracking service. Weak shaking is defined as being felt quite noticeably by people indoors, especially on the upper floors of a building, and may rock standing motor vehicles slightly.

About 7½ hours after the initial earthquake, a magnitude 4.0 aftershock struck roughly 12 miles away from the initial epicenter, the USGS reported. Shaking again was reportedly felt throughout the New York area.

Several smaller aftershocks had already been recorded, all around magnitude 2.0. But seismologists had said larger aftershocks were possible. The USGS had forecast a 78% chance of an aftershock of magnitude 3.0 or greater in the area in the next week, with a 99% chance in the next year.

Earthquakes in a sequence can be classified as foreshocks, main shocks and aftershocks. The main shock is the most powerful. Foreshocks occur before a large earthquake, while smaller quakes that follow are aftershocks.

It’s not until there’s a quake that is larger than the previous ones that an episode get “demoted” to foreshock and the main shock is identified.

The 7.4-magnitude earthquake that struck Taiwan on Wednesday can provide vital lessons for Southern California as it prepares for the next big temblor.

Earthquakes are less frequent and powerful in the eastern United States than in the West. Over the last half-century, more than 400 quakes of magnitude 3.5 or greater have been recorded across eastern North America, according to the USGS.

Shaking from a single quake in the eastern U.S. can be felt much farther away than an equivalently powerful magnitude quake in California.

Leslie Sonder, an associate professor of earth sciences at Dartmouth specializing in geodynamics, said the eastern U.S. typically experiences small and moderate earthquakes — and far less frequently than the West — because the nearest plate boundary is way off in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean.

Occasional earthquakes occur on faults formed when the Appalachian Mountains were created or when North America first drifted away from Africa and Europe about 200 million years ago, Sonder said.

“Because the rocks are old — basically nothing’s happened to them for 200 million years — they’ve cooled off and so they transmit seismic waves more efficiently than in the West, where the rocks are hotter,” Sonder said. “So that’s why they’re felt more widely in the East.”

In 2011, a magnitude 5.8 earthquake struck near Mineral, Va., about 300 miles from Friday’s temblor.

That quake — which produced more than 32 times more energy than Friday’s — resulted in severe shaking at the epicenter and caused more than $200 million in damage, including to historic structures such as the Washington Monument, the Washington National Cathedral and the Smithsonian Institution Building.

More recently, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake occurred in 2020 near Sparta, N.C., rattling northwestern North Carolina and southwestern Virginia.

Other historic damaging quakes in the eastern U.S. include one off Cape Ann, Mass., in 1755, estimated to be a magnitude 5.9, which resulted in damage to the Boston waterfront; an estimated magnitude 4.5 quake near Petersburg, Va., in 1774, which shoved homes from their foundations and was felt by Thomas Jefferson; and an estimated magnitude 7 quake near Charleston, S.C., in 1886 that killed 60 people, according to the USGS.

People are much more important than kits. People will help each other when the power is out or they are thirsty. And people will help a community rebuild and keep Southern California a place we all want to live after a major quake.

While California is the focus of national attention for its outsized seismic risk, a report issued by the USGS last year noted that the eastern U.S. faces risk too.

Calculating an “annualized” earthquake loss to average out the projected cost of earthquake damage on a yearly basis, the USGS found that the Memphis area faces an annual earthquake loss of $131 million a year, and the New York City region $49 million a year.

In any given year, New York City has a low probability of a damaging earthquake, but any quake could still cause significant damage because of the city’s density and age of its buildings, according to the city’s emergency management agency. A large number of older brick buildings have not been retrofitted, putting them especially at risk.

Benjamin Fernando, a postdoctoral fellow with the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Johns Hopkins University who studies seismology, said the New Jersey quake was probably on the Ramapo fault, a 700-million-year-old fault that runs through that state and hasn’t produced a quake of this size in quite some time.

“For people here in the Northeast, who are not used to events like this, it really calls people’s attention,” Fernando said. “But in California, people certainly wouldn’t get excited at all.”

Sally Taylor, a 77-year-old artist, said she felt the vibrations Friday morning in her apartment in Manhattan’s west 30s. When she wasn’t sure what the shaking was, relatives visiting her from the Bay Area said: “Nope, that was an earthquake.

”And that was nothing!” they added.

Sonder, the Dartmouth professor, said Friday’s quake was small, just starting to get into moderate size.

“This was significant in the social sense, because people felt it and they’re curious about it,” Sonder said. “But in a geological sense, it’s very generic. It’s maybe slightly bigger than a lot of the earthquakes in the East Coast. But it’s still no big deal geologically.”

Times staff writers Jarvie reported from Atlanta, Lin from Cleveland and King from New York.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.