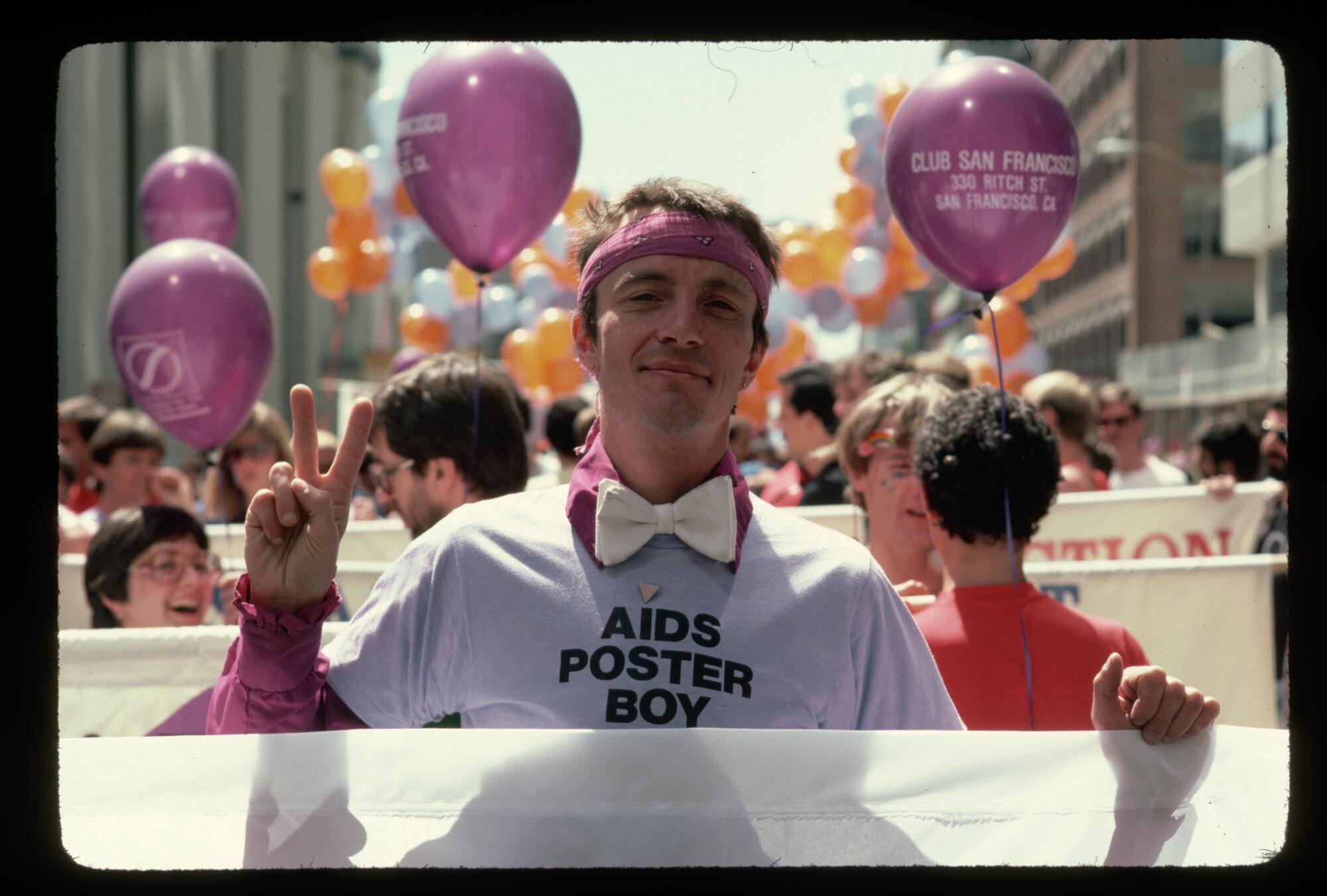

“I’m writing because I have a determination to live. You do, too — don’t you?” — Bobbi Campbell, “AIDS Poster Boy”

At no point did Bobbi Campbell ask for permission.

In 1981, the registered nurse took pictures of his Kaposi sarcoma (KS) lesions and posted them in the heart of San Francisco’s Castro District, along with a notice of his illness, to warn others. At the time no one could fathom the kind of global killer HIV would become. At the time, all anyone knew was it was impacting gay men.

With queer lives and culture under threat, Our Queerest Century highlights the contributions of LGBTQ+ people since the 1924 founding of the nation’s first gay rights organization.

Pre-order a copy of the series in print.

Campbell was the 16th person in San Francisco to be diagnosed with KS. The flier he hung in the window of Star Pharmacy was the nation’s first AIDS poster. That also made Campbell the first person in the country to publicly disclose his status. To understand how brave that was, consider the findings from a Los Angeles Times poll taken in 1985, a year after Campbell’s death.

More than half the country — 51% — supported quarantining AIDS patients in camp-like restrictions while 15% wanted patients tattooed. By this point more than 8,000 Americans had died, President Reagan was still avoiding the topic, and the White House spokesperson was making jokes about people dying of AIDS in public.

Many others, including popular comedians, were doing the same.

Along with this clear lack of compassion, nearly 35% of the country thought the queer community had too much political power. And, amazingly, in the face of that political and cultural headwind, is where Campbell volunteered to stand and fight.

During his three years as the self-proclaimed “AIDS Poster Boy,” Campbell was the target of both scorn and fear. Didn’t matter. He was relentless — combining his training as a medical professional and lived experience to try to educate a frightened public.

Shortly after Campbell learned of his diagnosis, he began writing a series of columns for the San Francisco Sentinel detailing what it was like living with the “gay cancer.” He did the “Phil Donahue Show” and ABC News. CBS followed him into a clinic for treatment. He helped write one of the country’s first safe-sex pamphlets for gay men and distributed it as a member of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.

His drag name was Sister Florence Nightmare.

In 1983, Campbell and his partner, Bobby Hilliard, graced the cover of Newsweek, arm in arm. In 1984 he was a keynote speaker at the National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights, which was held in San Francisco at the same time as the Democratic National Convention. There the Rev. Jesse Jackson became the first speaker to say the words “lesbians and gays” on a DNC stage.

“We’re not victims,” Campbell declared. “We are your children. And your mothers and fathers. And sisters and brothers.”

A hero’s journey often begins without knowing.

For Campbell, that first step was the night he met a small group of friends at the iconic Twin Peaks Tavern in the largely gay Castro. Among them was Cleve Jones, creator of the AIDS Memorial Quilt and co-founder of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.

“He took off his shoes and socks and showed us the purple spots on his feet,” Jones said, of Campbell’s Kaposi sarcoma lesions, a symptom of AIDS. “One of us had a Polaroid camera, so we took pictures that night and handmade the first AIDS education poster to warn people.

“I miss him. He was such a fun and loving person. And a true hero. He was out marching and giving speeches all the way up until his death.”

It would be easier to count the leaves of the giant sequoia than list the contributions of the LGBTQ+ community to the American way of life. From the first American woman in space to the creator of the 1960s soft drink “Fizzies” there truly isn’t a discipline or profession without a queer presence or aesthetic.

Perhaps in 1984, the year Campbell stood on the doorstep of the DNC to speak about the struggles of those living with HIV/AIDS, the lives of queer people were largely unknown. But to have hundreds of anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced 40 years later reflects willful hate — not blind ignorance. That’s what made Reagan’s handling of the AIDS crisis so insidious. Some of his friends from his days in Hollywood were queer. However, he chose disregard over compassion, and the country followed his inhumane lead.

LGBTQ+ representation in film and TV is essential. But the way we’ve come to define, discuss and quantify it leaves out too much of the queer contribution to culture.

From housing to employment, every aspect of life was touched by discrimination, in part because people living with HIV/AIDS were not protected by the Americans With Disabilities Act until 1990. In The Times’ 1985 poll, nearly 40% of respondents said they would want the government to spend more money if AIDS “mostly affected people who were heterosexual.” Only 32% approved of gay and lesbian equality as a civil right.

No one was coming to save us.

So, we had to save ourselves.

In doing so, we saved thousands of others.

It’s important to remember that part when reflecting on the epidemic. Trauma and loss do not tell the entire story. There were also heroes.

“At the end of 1985, everyone I knew was dead, dying or caring for someone who was dying,” Jones said. “I can’t think of another example in which the people who were inflicted and dying from the disease [were] also leading the fight. We were the caregivers, we became nurses. The young people of ACT UP, they are remembered for street demonstrations, but they also spun off the Treatment Action Group, which fast-tracked treatment with pharmaceutical companies and government.”

A hero’s journey often begins without knowing.

For Jones, that first step was participating in a hepatitis study conducted in San Francisco in 1978.

At the time, rates of hepatitis B were higher among gay men, so the Castro became a hub for volunteers and clinical tests. The research gathered there contributed to the development of a vaccine. Today there are far fewer cases, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention crediting vaccines with billions in medical and other cost savings globally.

Just a few years after Jones took part in those trials, the “gay cancer” made its presence known — and he reached out to those same physicians.

“I knew that there were samples of my blood that had been stored, and I knew people who were involved with that study,” he said. “So, I called them up, and it turned out that one of the men who was running the study had been a roommate of mine years before. He took me out to lunch and said, ‘What do you think?’ and I said, ‘I think I’ve got it,’ and he said, ‘You’re right.’ ”

Jones had been living with the virus since 1978 but did not see symptoms until 1992.

“By 1994, I was beginning to give up,” he said. “It was exhausting. Every sneeze, every cold came with anxiety. It brought out the best in some of us and the worst in others.”

Jones was almost gone when Dr. Marcus Conant, another San Francisco AIDS Foundation founder and the physician who diagnosed Campbell years before, was able to get Jones into the medical trials that ACT-UP had pressured the government to expand.

“There was a generation of gay men who volunteered to be guinea pigs with no information about the side effects,” Jones said. “They are heroes. All of them. Because of their courage, we saved ourselves and everyone else too.”

Just as the research done with the help of the LGBTQ+ community led to the hepatitis vaccine, society has the tools to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS because the queer community led the fight to find them. Today pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) prevents the spread of HIV from sex or injection drug use when taken as prescribed.

By 2014, the chief executive of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation told Time magazine, “I don’t think it’s outrageous or unrealistic to say we have the opportunity to be the first city to end HIV transmission.”

The Castro was once the epicenter of the disease. It is now another example of the resolve of queer people. The reason efforts to erase us from history fail is that there is no history without us.

It is not an overstatement to suggest World War II may have turned out differently had Alan Turing not been able to crack the encrypted messages that enabled the Allies to defeat the Axis. What becomes of the civil rights movement if Bayard Rustin isn’t there to mentor the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on the principles of nonviolence or organize the March on Washington?

People who exist at the nexus of multiple movements for liberation are the ones who drive us forward, treating the struggle for equality with urgency.

Among the passengers on United Airlines Flight 93 who stopped the hijacked plane from reaching its target the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, was a 6-foot-4, 225-pound gay rugby player by the name of Mark Bingham. Before attacking the terrorists on board, the 31-year-old called his mother.

“He just called and said, ‘Mom, I want to tell you that I love you,’ ” Alice Hoagland said. “ ‘Three guys have taken over the plane and they say they have a bomb.’ ”

That was the last time she heard his voice.

Daniel Hernandez also called his mother soon after a gunman opened fire at an event hosted by former U.S. Rep. Gabrielle “Gabby” Giffords, critically wounding the congresswoman.

“Mom, don’t worry about me … I’m fine ... but something’s happened to Gabby… It’s bad … I have to go.”

Hernandez, also gay, was a 20-year-old intern at the time. It was his first week on the job. His actions helped save her life.

Just as the actions of Capitol Police Officer Crystal Griner saved the life of Rep. Steve Scalise and many others in the summer of 2017. Republican members of Congress were at a baseball field just outside of Washington, practicing for a charity game. Scalise was standing at second base when a lone gunman opened fire. He was struck in the hip. Officer Griner, who is a lesbian, was also shot — in the ankle — before she and Officer David Bailey stopped the gunman.

“Many lives would have been lost if not for the heroic actions of the two Capitol Police officers who took down the gunman despite sustaining gunshot wounds during a very, very brutal assault,” then-President Trump said, back when he liked the Capitol Police.

On the day Campbell spoke at the rally outside of the DNC, he called for a moment of silence for 2,000 people who had died.

When the wind picked up, Hilliard lovingly helped him hold the pages of his speech. The two shared a kiss on stage. Campbell said he wanted to show America what love looked like. One could argue that the two of them simply standing side by side in the sunshine was demonstration enough.

A month later Campbell was gone.

He would have turned 72 in January.

There is a plaque in San Francisco honoring his contributions, but I would argue Campbell’s true legacy is the more than 500,000 Americans over the age of 50 currently living with HIV.

A tribe I am grateful to be part of.

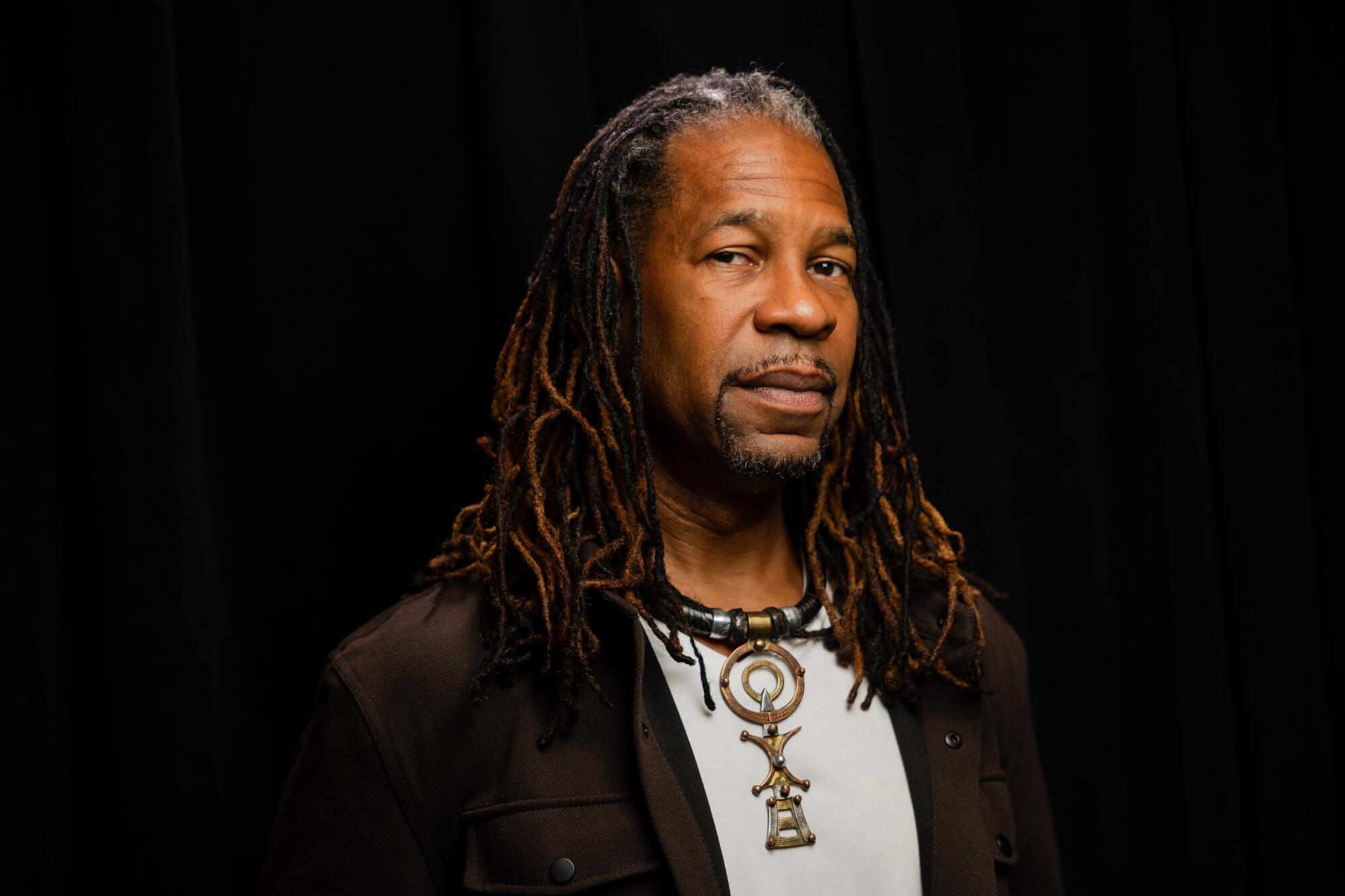

I too am HIV-positive — and this is the first time I am sharing this information publicly.

My viral load has been undetectable for years, meaning I cannot spread the virus to others. Except for my arthritic hip — a byproduct of years of basketball — I feel fine. The only time I’ve thought about my mortality in recent memory was at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when most everyone was thinking about life and death.

Still, I’d be lying if I didn’t admit shame was a significant factor in my keeping my status quiet until now. I didn’t want to be viewed as a gay stereotype, including at ESPN, where I worked for years. I was not the first openly gay person there, but I was among the most visible, and that came with scrutiny. I also kept my status private because I didn’t want to be shunned in social settings. The use of the word “clean” on dating apps served as a regular reminder that the epidemic may have subsided, but ostracism remained.

I didn’t want any of it.

But then again, no one wanted any of it.

In Campbell’s first column for the Sentinel, he explained why he was disclosing his diagnosis to the world: “I’m doing this for me, I’m doing this for you, and I’m doing it for our hypothetical brother standing on Castro Street who has ‘gay cancer’ and doesn’t know it. He may also be standing on Christopher Street or Santa Monica Boulevard, and he’s probably not hypothetical… I’m writing because I have a determination to live. You do, too — don’t you?”

In that same spirit, I am writing because I have a determination to live — and I want you to, as well. To quote Grammy-winner J-Cole: “Made it out, it gotta mean somethin’.” The goal in sharing my status is to shed light on both the virus that is still a threat, and the means we have to end that threat once and for all.

At the onset, AIDS may have been characterized as a white gay man’s disease, but in 2021, women made up nearly 20% of new HIV patients. And of that group, more than 50% were Black women, despite their making up only about 15% of U.S. women overall.

Over the past 100 years, LGBTQ+ Americans have forged a path through history. Here are some highlights.

The disease is no longer on the news, but tens of thousands are still being infected every year. Thousands are dying — and it doesn’t have to be this way. Not anymore. HIV is a chronic disease much like diabetes. It’s the shame associated with the virus that enables it to keep spreading and killing. It’s the shame that prevents people from asking for help. Only 11% of Black people who could benefit from PrEP were prescribed it, and only 20% of Latinos. That number is nearly 80% for our white counterparts.

Barriers such as cost are one factor. Physicians tell me fear of being judged is another.

All of which brings me here: The first person known to have died of AIDS in this country was a 16-year-old Black kid from St. Louis by the name of Robert Rayford. He had been feeling ill since 1966 but didn’t go into the hospital until 1968. By then his skin was pale, he was having trouble breathing, and his legs were covered with open sores.

For more than a year, Rayford’s condition worsened. Doctors didn’t know what was ailing him or how to provide relief. The teen eventually died alone in a hospital bed in 1969, one month before the Stonewall Riots. It wasn’t until 1987 — after tests were performed on saved tissue — that doctors learned Rayford’s open sores were KS lesions and that he had been suffering from AIDS.

Today, Black men contract the virus — and die from it — more than any other group. We don’t have to. Today, it’s not just about getting treatment. It’s also about pushing beyond fear to save our own lives.

A hero’s journey often begins without knowing.

For me, that journey began when I got tested, learned my status and started taking my prescriptions. Two pills with coffee every morning. Sometimes orange juice. I didn’t know it at the time, but that’s when I became my own hero.

That’s why I wrote this essay.

I have a determination to live.

My hope is that you do too.

Find all our essays, illustrations, poll stories and more in a single keepsake print edition.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.