The dead body in the bedroom told a story of savagery and rage.

Twenty-nine stab wounds, including some through the skull — one so vicious the tip of the knife broke off. Blood soaked her slashed floral nightgown, drenched the rug, splattered the walls. A bite mark pierced the back of her shoulder, teeth sunk into flesh as she tried to flee.

In the early hours of July 7, 1985, Connie Dahl and her boyfriend called police in a panic after they returned to his house following a long night of partying and discovered the murder of a houseguest. They had no idea what had happened, Dahl told detectives. Only that they had walked in on this scene.

The El Dorado County sheriff’s deputies quickly began to question that story. Dahl, 19, and her boyfriend, 20-year-old Ricky Davis, became suspects instead of witnesses.

For the next 29 years, Dahl’s life was slowly crushed by the body in the bedroom — first by the trauma of finding the mutilated woman, then by the accusations that Dahl was involved.

More than a decade later, Dahl would crumble under the relentless questioning of detectives who made false statements about the evidence, and the tricks of her own mind that left her believing that she was involved in the killing — that she was, in fact, the biter whose teeth had sunk into the woman’s back. After a series of manipulative interrogations over a period of years, Dahl falsely confessed that she had participated in the murder.

She told that same false story in court, identifying her ex-boyfriend, Davis, as the killer and sending him away for 16 years to life. She was jailed for four years, before returning home to try to pick up life with her young children.

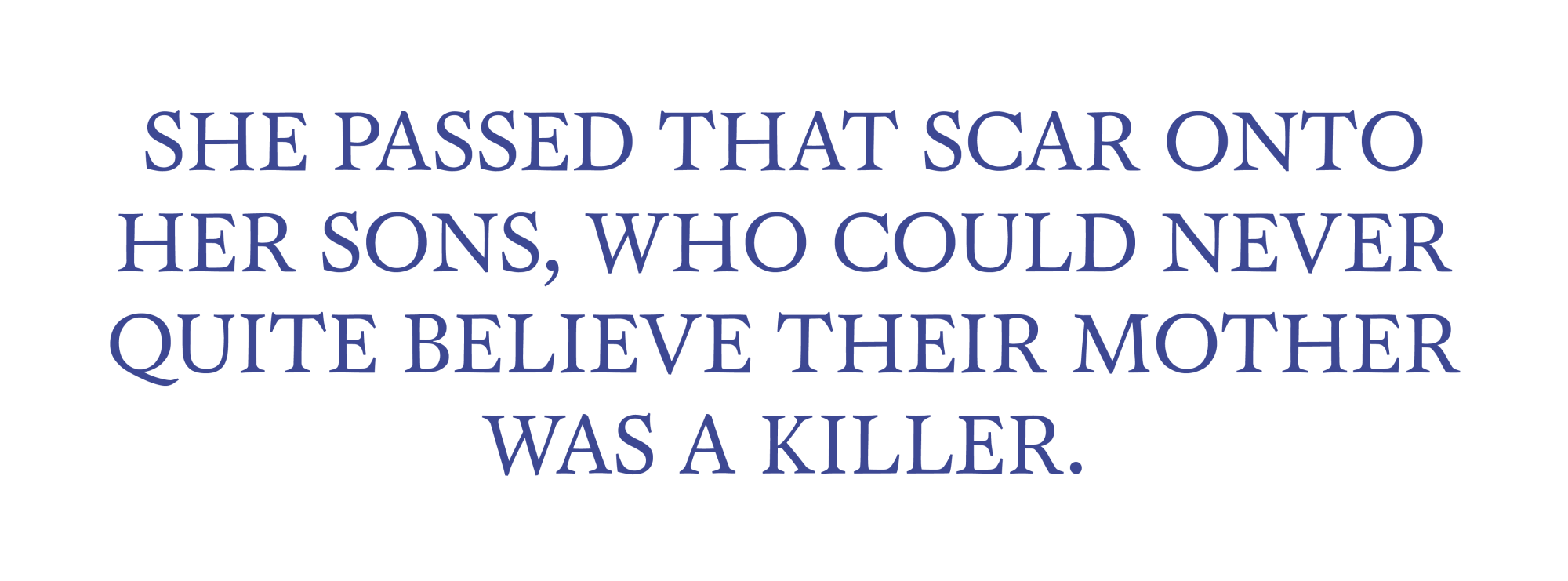

But she could not escape that terrible image of herself, the consequence of a method of policing that allows detectives to deceive and threaten in pursuit of a confession. And she passed that scar onto her sons, who lived with her addictions and chaos, but still could never quite believe their mother was a killer.

They were right.

In 2020, Davis became the first person in California ever to be exonerated based on genetic genealogy, the use of family trees to track down an identity from unknown DNA samples.

Dahl had died six years before, still a convicted killer. No one remembered to clear her name.

“It really kind of destroyed my childhood,” said her youngest son, Jarred Lange, of her arrest and conviction. “Everybody disowned and gave up on her, because she was associated with murder.”

On Friday, El Dorado County Dist. Atty. Vern Pierson asked the court to posthumously exonerate Dahl and find her factually innocent. He moved to formally clear Dahl’s name after Times reporters informed him of the pain her record still caused her family.

Pierson said it is a necessary piece of accountability, overlooked and overdue.

“Sometimes you make a mistake,” he said. “The public loses trust and confidence when we don’t own up to mistakes and take responsibility.”

For Pierson, the exoneration is about more than righting the harms of a wrongful conviction. The story of how Dahl went from being a troubled teenage party girl to a convicted murderer, he said, highlights a “coercive” and “dangerous” interrogation practice in American policing that needs to be replaced with a modern, evidence-based approach.

The method incorporates a strategy that many detectives in the U.S. have been trained to use. Investigators are taught to develop a theory of the crime, then to pursue a confession from their suspect, even if it means using untruthful interrogation techniques. The method has been heroically featured in cop shows and films for decades, and properly used, defenders say, it elicits the truth from criminals who are lying. But Pierson and other critics say it can also cause innocent people to confess to things that aren’t true.

More than once, the wrong person has ended up behind bars.

Summer 1985

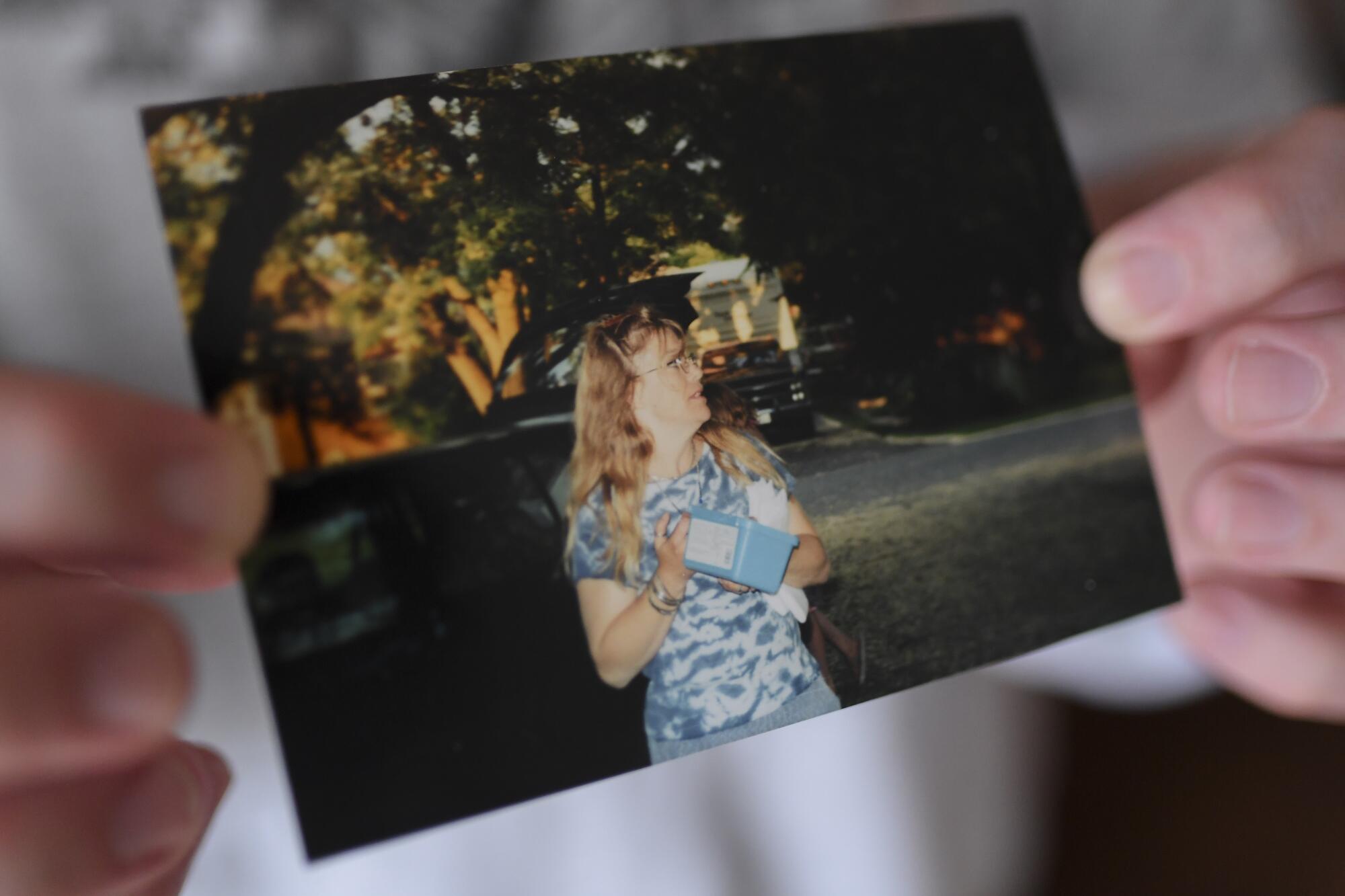

On the day her life fractured, Connie Dahl, who had long blond hair and a wild sense of humor, worked an early shift as a hostess at Sam’s Town, a kitschy spot near the small town of Placerville with sawdust on the floors and an arcade to keep kids busy while their parents drank.

After work, as was true many days, she passed the time listening to heavy metal and inhaling drugs — methamphetamine, marijuana or coke.

Dahl’s family had recently come to California from Oregon to offer emotional support for her aunt. The previous year, the aunt’s daughter had been murdered, and the trial was about to begin. It was a stressful time, and Dahl was fighting with her aunt constantly. She began staying with her new boyfriend, Davis, in his mother’s house in a posh new development in the hills. Davis was a sometime-construction worker who had a history of run-ins with police but also an easygoing charm and pot plants growing in the backyard.

Dahl wasn’t exactly welcome — she had to sneak in through a window to avoid Davis’ mother. But she tried to be a good guest. She sometimes did the dishes, even after getting high in the downstairs bedroom.

On the afternoon of July 6, two other guests arrived at the house: Jane Hylton and her 13-year-old daughter, Autumn Anker. Hylton, 54, a friend of the Davis family, was a vivacious local newspaper columnist who had left her husband and needed a place to stay.

That evening, Dahl and Davis headed to a party about 10:30 p.m. Hylton was in the living room reading a book. Autumn had gone out to explore the neighborhood.

Dahl and Davis got back to the house a little after 3:30 a.m., after drinking all night. Before they could get inside, Autumn came out of the shadows in the front yard and asked for help. Autumn, too, had spent the evening drinking, with three boys she had met in a nearby park. She was drunk — but not so drunk she wasn’t aware that if her mother caught her, she would be in big trouble.

Davis offered to usher Autumn into the house and to tell her mother, if asked, that the teen had spent the evening with them.

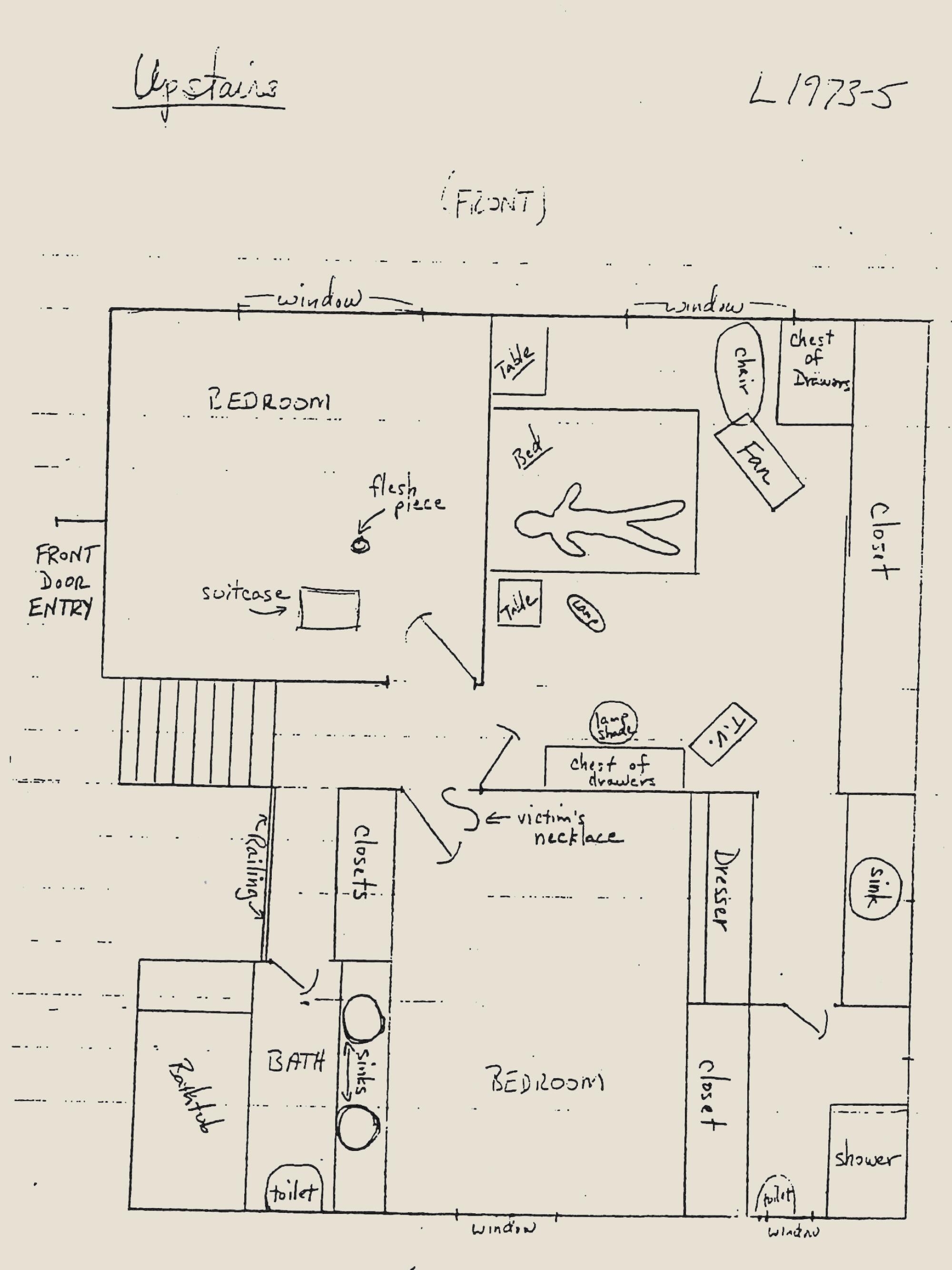

Dahl noticed, as they entered, that the front door was open and downstairs lights were still on. They proceeded upstairs stealthily. Dahl helped Autumn into bed.

Davis, meanwhile, paused outside the master bedroom. When his mother was out of town, as she was this weekend, Davis often slept in her bed. But the door was closed. Did that mean Hylton was inside?

He turned on a light. “And that’s when I seen all the blood,” he told police a few hours later.

Detectives have a hunch

El Dorado County Sheriff’s Det. Bill Wilson and his partner, Det. Larry Hennick, arrived at the crime scene within the hour to interview the still-drunk trio.

All three told essentially the same tale: They had come home in the early hours. The door was open. They entered and went upstairs, whereupon Davis discovered Hylton’s desecrated body.

As the detectives listened, they took note of small discrepancies. For example, Davis told police he had called 911. Then, Dahl said she had, while Davis was still upstairs.

Wilson and Hennick swiftly focused on one suspect: Davis.

It was plausible to them that he was pressuring Dahl and Autumn to cover for him. That would explain the slight discrepancies in their memories: Davis had crafted their story, and they weren’t reciting it quite right.

The detectives set about trying to break Autumn and Dahl and get them to admit to the cover-up — despite a lack of evidence or even a murder weapon.

But during ensuing weeks of interrogation, without legal representation, Autumn, Dahl and Davis stuck to their stories.

Autumn described the three boys she had met that evening in the park, but could offer few details except two first names and one full name: Calvin, a guy named either Steven or Brian, and Mike Green. Investigators showed little interest in them, instead pressing her to admit she knew Davis was the killer.

“You know Ricky’s lying?” Hennick said, according to an interrogation transcript. Then later: “And we know now. And we want the truth.”

“Ricky’s a violent guy,” he added. “He attacked a man with a tire iron one time, because he was upset with him. I’ve known Ricky a long time. So does Bill. We know what he’s capable of.”

In one interview, Hennick tried to make it seem that if Autumn were involved, it wasn’t her fault and it was in her interest to turn in Davis.

“You were so frightened,” he said to Autumn. “You just saw Ricky kill your mom with a knife, and you know that he could do that to you if he wanted to.”

Wilson took a softer approach. “Let me tell you what I think,” he said. “You either know what happened or you were there when it happened.”

At this, Autumn began to sob. “I wouldn’t let my mom get murdered,” she said.

Things didn’t go much better with Dahl.

Wilson falsely told Dahl that police had found Davis’ blood on clothes at the scene of the crime, according to the transcripts. “And something else,” Wilson added. “The hair that’s in [Hylton’s] hands is Rick’s.”

“No way,” Dahl shouted. “You cannot pin this on Ricky, because I was with him all night long.”

“You watch,” Wilson answered.

A cold case reopens

More than 14 years went by without an arrest.

Autumn grew up, got married and had a child — all under the shadow of her sisters and brother believing, as police had told them, that she had helped kill their mother.

Davis continued to have run-ins with the law, including a conviction for bank robbery that sent him to federal prison.

Dahl returned to her native Oregon and had two sons and tried to build a life for them. But the image of the body in the bedroom wouldn’t fade.

In November 1999, two El Dorado County detectives, Richard Fitzgerald and his partner, Richard Strasser, showed up in Eugene to grill Dahl about the murder once again.

In the late 1980s and into the 1990s, police departments across the country began creating “cold case” squads, detective units that would dig into old unsolved murders. In El Dorado County, the open cases included dozens of slain girls and women, Hylton among them.

Fitzgerald, a onetime airline baggage handler who had become one of the department’s most dogged detectives, was determined to solve it.

“So why don’t you tell me what really happened?” Fitzgerald demanded during his first interrogation of Dahl, according to the transcripts.

Dahl: “That’s what happened. That’s all I know about that.”

Fitzgerald: “But that’s not what happened.”

Dahl: “What do you mean?”

Fitzgerald: “We already know that.”

Dahl: “What do you mean?”

Stuck again in an interrogation room, Dahl gave answers that suggested she was starting to wonder — about the past, about her memory, about her sanity, about her innocence. After years of drug use and hard living, what happened yesterday could be tough to remember. What happened more than a decade ago was downright hazy.

She told Fitzgerald he was confusing her, and she was scared. She needed a cigarette and to pee.

Like the original detectives, Fitzgerald professed over and over again that all they were after was the truth.

“We want to get this thing right,” he told her. “We’re just simply here to talk to get information.”

But they also told Dahl they had evidence she was involved in the murder, and once again treated her as a suspect rather than a witness.

Fitzgerald: “We know that, that you were present in the house when this happened.”

Dahl: “Oh, no I was not.”

Fitzgerald: “But we already know that.”

Dahl: “Ha, what do you mean?”

Fitzgerald: “Well, like I said, you know, we’ve got all kinds of physical evidence and tests and everything else.”

Dahl: “I was there when it happened?”

Fitzgerald: “Yes.”

Dahl: “Oh, my...There’s no way.”

That evidence never materialized, despite Fitzgerald’s ongoing claims. And, for a time, Dahl held firm.

The weak link

Back in California, the detectives confronted Autumn, now 28, employing the same tactics they had used to confuse Dahl.

“I expected you to be some crack whore in San Jose or something,” Fitzgerald told her, according to an interview transcript.

“I told Autumn that we now knew the true story,” Fitzgerald later wrote in his police report. “We knew she was part of her mother’s murder.”

But unlike Dahl, Autumn’s life had stabilized. Her memories were certain and her response unequivocal: “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

Detectives also re-interviewed Davis, who was still in federal prison on the bank robbery charge. They showed him gruesome photos from the crime scene. But like Autumn, he maintained his innocence.

Detectives homed in on Dahl as the weak link. They returned to Oregon in January 2000 and February 2001.

Dahl’s worry for her two boys deepened with each interrogation. Whether she believed in her own guilt or was confused by the tactics and threats and a clouded memory, she worried that her children were in danger of losing their mother — no matter what she said.

“And they are the main reason why I talk to you, because I love [my kids] more than anything,” she told the detectives.

Dahl had been labeled a liar before. For years, she had said she was sexually abused by a family member when she was a child. Some of the family didn’t believe her, leaving her feeling outcast and distrusted.

That left her vulnerable, and Fitzgerald and Strasser finally found a detail that struck Dahl deep in her psyche.

Hylton had been bitten on the back of her shoulder, Strasser told her in one interrogation. The revelation brought Dahl up short; she had been in physical fights in her rough childhood, and had used her teeth as a weapon.

“I’ve bitten a couple times,” Dahl told them.

The bite mark struck Dahl as proof maybe she had been involved and repressed memories from that night. The detectives seized on the opening. Fitzgerald told her that Davis had “programmed” her with false memories and he could help her bring forward the real ones, according to the interrogation transcripts.

He pressed on, saying she had never attended any party the night of the murder, the alibi she and Davis gave police. He said he had interviewed “a hundred” people who assured him she hadn’t been at the party. He told her she, Davis and Autumn had likely murdered Hylton early in the evening and spent the night making up their story before calling police.

Fitzgerald: “So you didn’t go to the party.”

Dahl: “How’d I get drunk?”

Fitzgerald: “Why would you go to the party after this happened, and then come home and call the cops?”

Dahl: “Ah, you’re right, so…”

Fitzgerald: “Think about that.”

Dahl: “Okay.”

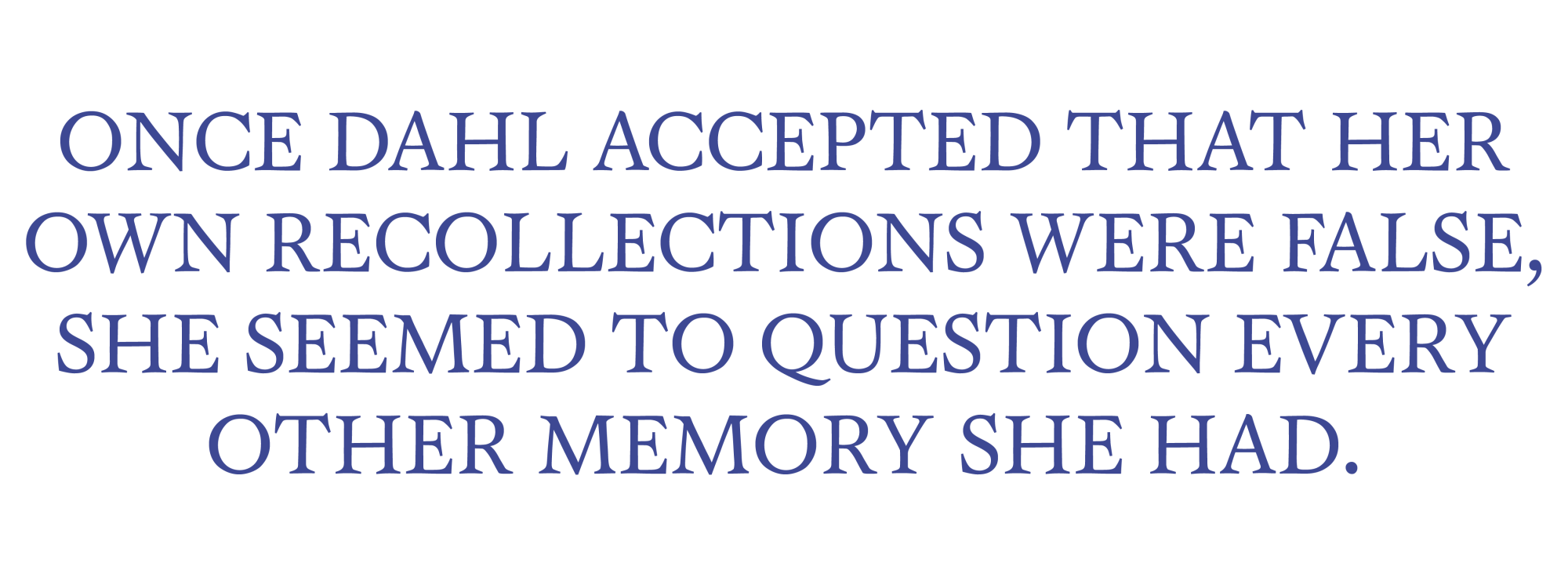

Once Dahl accepted that her own recollections were false, she seemed to question every other memory she had of that night. Her story began to match the police narrative.

Fitzgerald: “You were there. You saw it…”

Dahl: “Okay, wait a minute. I’m, I’m gonna … I’m trying to remember. I, I, you know what, I think they did get into an argument up in the, up in top but … I’m so confused about this.”

Fitzgerald: “You’re not confused. You’re afraid to tell us the truth.”

Then later:

Fitzgerald: “You’ve been looking forward to this day for 15 years, if you’ll stop and think about it and be honest with yourself. You’ve looked for the opportunity to tell the god-damned truth and that’s why we’re here. You know you saw this. You know you know what happened. It’s all over with. You’ve got your babies. What are you gonna tell your … What are you going to teach those kids?”

Over and over, during the interrogation, Fitzgerald told her his version of events: If she were present, she must have gotten blood on her. If she had blood on her, she must have washed it off. Where did she wash it off? Just think, just remember.

“See, I’m not trying to give you answers,” he told her at one point, as she struggled to find memories that worked in this new narrative. “I’m just trying to use common sense.”

On May 21, 2002, El Dorado County prosecutors charged Davis with murder, relying mostly on Dahl’s statements. They charged Dahl with manslaughter.

Dahl would be held without bail in El Dorado County jail until she testified against Davis, a trial that would not happen for three years.

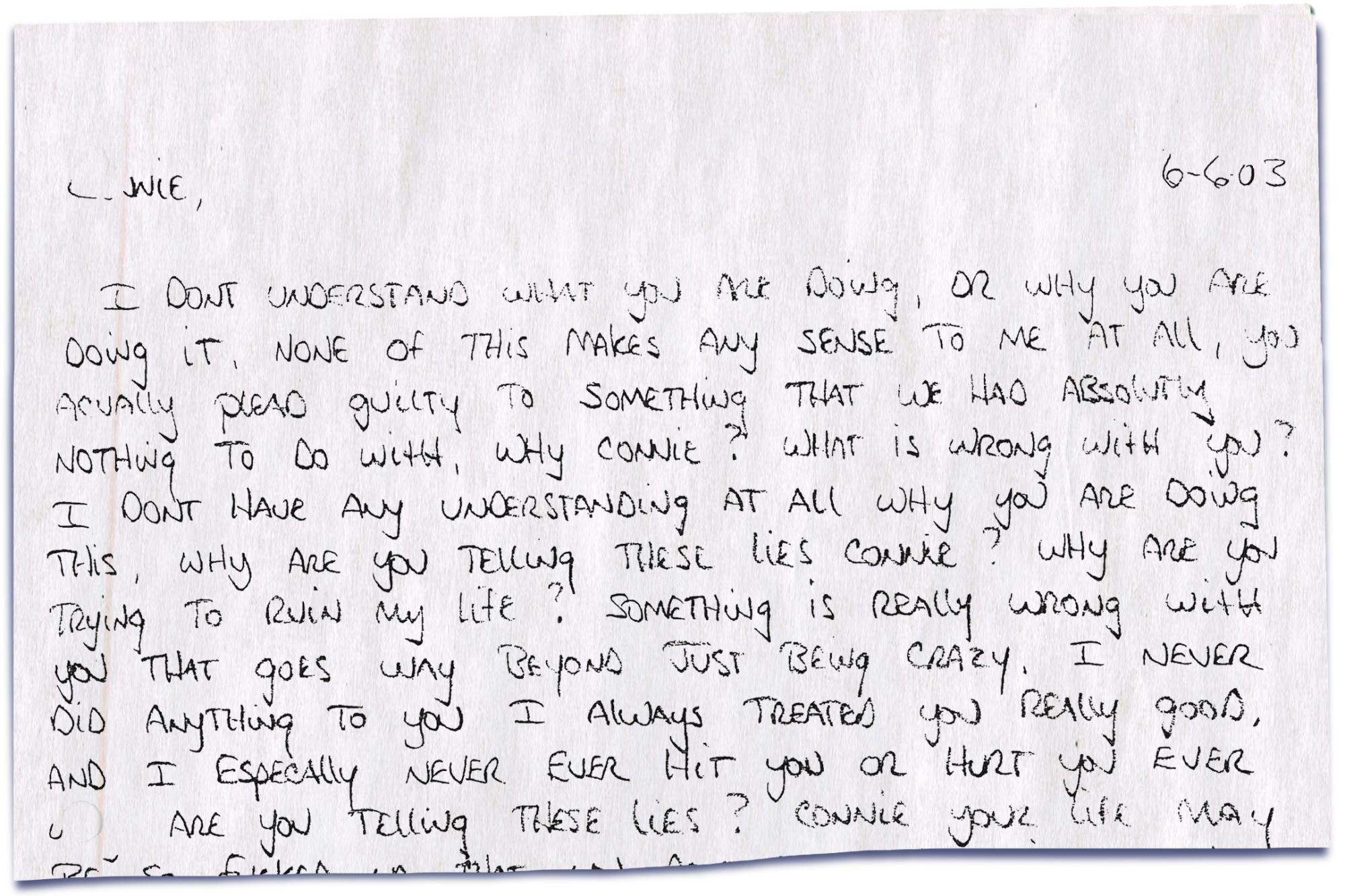

As the legal proceedings moved forward, Davis wrote multiple jailhouse letters to Dahl, veering from anger to confusion, pleading with her to change her story.

“I don’t know what the detectives did or said to you to tell these lies, but I’m begging you to just please tell the truth,” he wrote in June 2003. “Why are you doing this to yourself and to me? You know we are absolutely innocent.”

In August 2005, Davis was convicted of murdering Hylton and sentenced to 16 years to life.

Dahl pleaded no contest to voluntary manslaughter. She was released in 2006 and allowed to return to Oregon on probation.

Fitzgerald and Strasser received an “Investigative Excellence Award” from the state Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training for closing the case.

An uneasy prosecutor

Mired in prison with little hope, Davis began writing more letters — thousands of them. To the media, to lawyers, to family.

They all said basically the same thing: He was innocent. He had been framed. He needed help.

Melissa Dague O’Connell, a lawyer with the Northern California Innocence Project, finally took notice in what would become a 10-year quest to free him. What struck O’Connell was the lack of physical evidence implicating Davis. The conviction had relied largely on Dahl’s testimony.

O’Connell brought the transcripts of Dahl’s interrogation to Pierson, a Republican D.A. in a conservative county and a man known for tough justice.

Pierson was a prosecutor through and through, and didn’t subscribe to the notion that there were huge numbers of innocent people in prison because of the sloppiness or zealotry of law enforcement.

But he also hated deception, and had long been troubled by some detectives’ belief that the best way to get suspects to confess was to lie to them, an interrogation method commonly taught in training courses and a practice passed down from older investigators.

When Pierson read the transcripts from Fitzgerald and Strasser’s interviews with Dahl, he felt a drop in his stomach.

“I was like, ‘I just don’t like this interview. It just bothers me,’” Pierson told The Times.

As he read through page after page of questioning, Pierson said, he thought Dahl was being worn down. She “adopts what they are suggesting to her. And when factually, she gets an element wrong … they correct her. And then she adopts that.”

It was not the first time a leading interrogation had caused Pierson discomfort. As a young prosecutor, he had watched detectives interrogate a suspected pedophile. During that interrogation, the interviewer had made it seem as if he understood that perhaps the young victim was complicit. Pierson thought it was wrong, disrespectful to the child who had been brutalized.

He agreed with O’Connell that the surviving physical evidence in Hylton’s murder should be tested for DNA.

Though police logs showed multiple strands of hair had been found clutched in Hylton’s hand — presumably ripped from the head of her attacker — the strands could no longer be located. What remained in the evidence room was a piece of fingernail torn off Hylton’s hand during the struggle, and the bloody remnants of her floral nightgown, so damaged it was nearly impossible to tell where the bite had torn cloth.

O’Connell and Pierson turned to criminalist Angelynn Shaw, the same Sacramento DNA expert credited with performing the forensics that brought Golden State Killer Joseph James DeAngelo to justice.

Working in her spare time over a period of years, Shaw went to work on Hylton’s nightgown. She extracted traces of DNA from the tear in the back left shoulder where the attacker had bitten Hylton and a related partial DNA profile from the fingernail. From these, Shaw discovered the DNA on Hylton was not from Dahl, Davis or Autumn.

They had an unknown male killer.

Pierson turned to his most trusted cold case investigator, Joe Ramsey.

“I want you to pretend Ricky isn’t in custody. I want you to pretend that this trial never took place, and that you’re looking at this case like it’s a cold homicide, and you’re reinvestigating the case, like it’s a new case,” he recalled telling Ramsey. “Can you figure out, if he didn’t do it, who’s the real killer?”

Ramsey combed through files and re-interviewed witnesses. He went back to Autumn, who made the same request she had been making since the night of the murder: Find the boys I was with that night. Maybe they can tell you something.

Just bring me a yearbook photo and I can identify them, she told Ramsey. Why, he wondered, had no one done as she asked?

Ramsey knew from Autumn’s description that one of the boys — Michael Green — was Black, a rarity in the mostly white community, especially in the ‘80s when the killing occurred. He went to the local high school and pulled yearbooks. There, in the 1985 Oakmont High yearbook, he found a Michael Green.

Autumn identified the photo instantly.

Killer in plain sight

Working with Autumn’s statements, Ramsey was quickly able to identify the other boys she was with the night her mom was killed.

The “Calvin” she first reported was Kelvin Beckham, “Steven” was Steven Gray, a close friend of Green’s at the time.

When Ramsey tracked down and spoke with Gray, he seemed unsurprised that police had finally arrived. He told a story that matched what Autumn had told police from the start: The boys had met her in a park.

According to court records, Gray told investigators that he and Green got separated from Autumn and Beckham later that night, and eventually separated from each other. In the morning, Gray said, he woke to find Green had returned to Beckham’s house and was asleep in a blood-soaked jacket. Later, he told investigators, he saw Green washing clothes in a kiddie pool in the backyard, the water red with blood.

At first, Gray told police, Green professed he was covered in blood because he had “sacrificed a rabbit to Cthulu,” a malevolent god-like entity with an octopus head created by the writer H.P. Lovecraft in 1928. The boys were into Dungeons & Dragons and had talked about Lovecraft’s books.

A few days later, according to court records, Gray saw an article in a local paper about Hylton. He told investigators that he and Beckham confronted Green and that Green confessed he had killed her. But he said they never reported it to police.

Ramsey needed more.

Green was living just miles from the crime scene, in Roseville, a foothills suburb known for its good schools and gated communities. He had a son and cared for his aging mother in the quiet cul-de-sac where he was raised. People on his street knew him as a nice guy.

Authorities had a new investigative tool honed during the Golden State Killer case: tracing DNA samples using online ancestry sites. Investigators uploaded the genetic information taken from Hylton’s nightgown to GEDmatch and found multiple relatives.

They followed the family tree back to Green.

In January 2020, police collected Q-tips, straws, drink containers and a napkin from Green’s trash. Forensic analysts were able to match a sample taken from a Q-tip to the DNA on Hylton’s nightgown.

Police finally had the real killer.

When officers arrested Michael Green, he confessed, according to multiple court records, including a psychologist’s report.

Green, 17 at the time of the killing, said he had gone to Autumn’s house looking for his friends and entered the unlocked front door after knocking and hearing a voice telling him he could come in. He climbed the stairs and entered Hylton’s bedroom. Both were shocked by the other’s appearance.

Green told an investigator that Hylton yelled at him and grabbed his shirt and that’s “when everything went sideways.”

Green said he was kicking at Hylton and they fell to the ground. He landed inside the room — Hylton was between him and the door. Green’s fixed-blade knife, which he routinely carried, fell to the floor. Hylton picked up a lamp and hit Green, and Green grabbed the knife.

Green told the investigator he remembered stabbing Hylton only once, but knew he had done it multiple times. Court records show that two of those blows punctured her lungs. One cut her jugular. Four went into her skull, and five were to her back. The rest she tried to block with her hands.

He told a psychologist hired by the defense that he ran out of the room as soon as she stopped hitting him, leaving Hylton on the floor, slumped against the mattress.

He dropped the knife in a nearby trash can, went back to his friend’s house and slept. He said he didn’t think about the stabbing much again.

Later, he seemed to struggle to explain his motivations. He told the psychologist that “it was just a horrible incident. It should never have happened. I would take her place if I could help her family with the hurt.”

As to Davis spending 15 years in prison for a crime he did not commit? Green called it “a bummer.”

He pleaded no contest to second-degree murder, and in 2022, at age 54 — the same age Hylton was when she died — was sentenced to 15 years to life.

Long overdue

In February 2020, the day Green was arrested, Pierson drove to his county jail, where Davis had been transferred.

By that point in his life, Pierson, a former Army combat marksman, had been a prosecutor for 30 years. He had argued more than 100 trials before a jury, including convicting the husband and wife who had held Jaycee Lee Dugard captive for 18 years in one of California’s most notorious child abduction cases.

He had seen a lot of crazy stuff. A lot of evil stuff. A lot of stupid stuff. He had put a lot of people in prison for a long time.

And this, he thought to himself, was “one of the most surreal moments I’ve had as a prosecutor.”

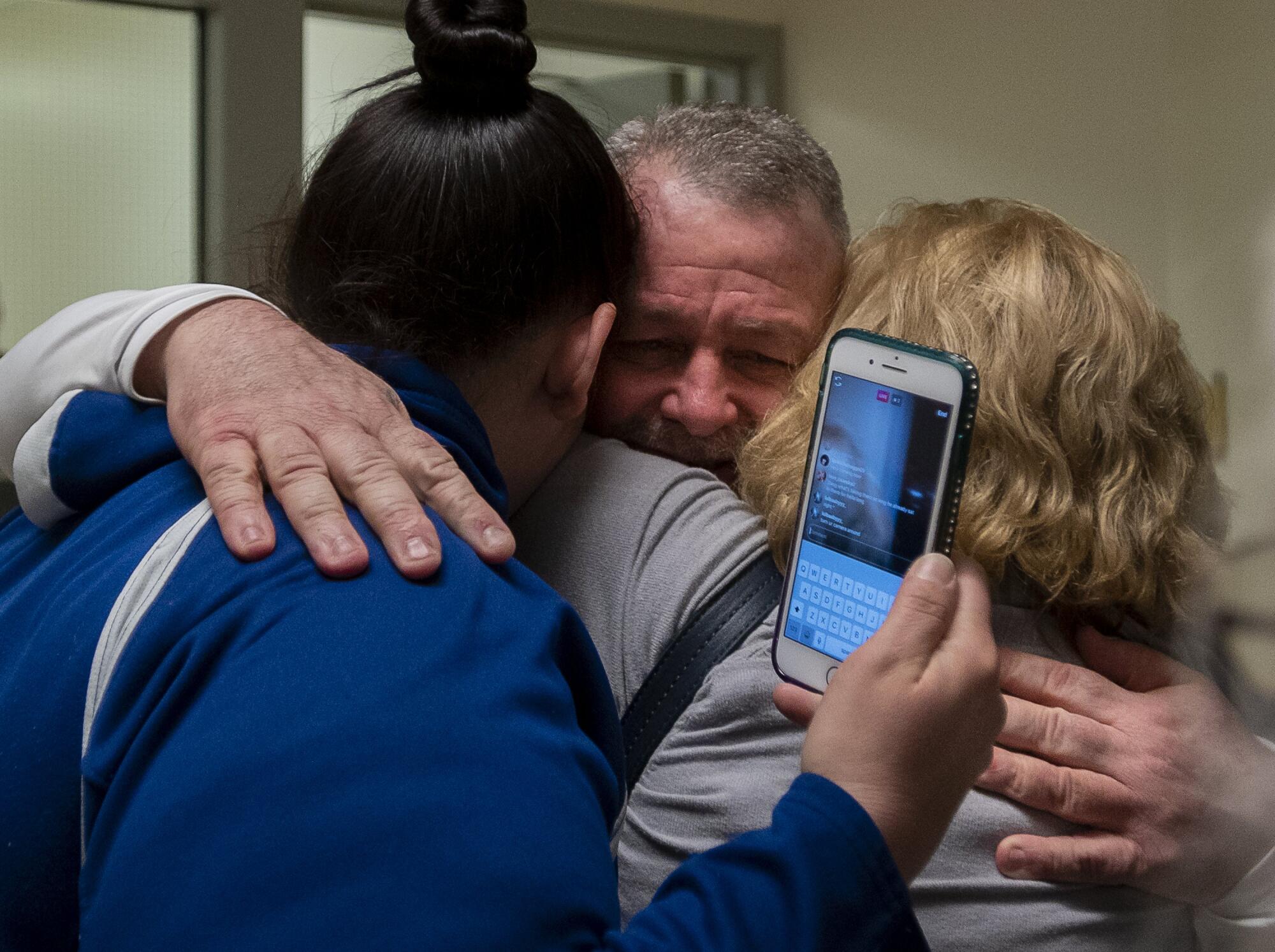

He stepped into Davis’ cell and looked him straight in the eye. “I’m sorry,” he told him. “And I’m going to get you out of here.” Davis began to cry.

“He kept telling me he didn’t do it,” Pierson recalled. “I said, ‘Rick, I know you didn’t do it, because we’ve got the guy who did.’”

And Pierson made Davis a promise: I’m going to change the way law enforcement is trained in America.

The detectives who pursued him, Pierson told Davis, weren’t bad people. They were following their training.

“I made a commitment,” Pierson said. “I’m going to change the way we train law enforcement, and how detectives specifically do interviews and interrogations.”

On Feb. 13, 2020, Davis walked out of jail — not just free, but factually innocent.

Davis, who has struggled financially since his release, has sued El Dorado County, seeking millions of dollars in restitution. He has also sued the detectives.

The original detectives, Wilson and Hennick, are deceased. Fitzgerald hung up on a Times reporter seeking comment. Strasser did not return calls and a text seeking comment.

But in their response to Davis’ lawsuit, Fitzgerald and Strasser deny wrongdoing. They argue that, in addition to having qualified immunity, their actions did not “constitute intentional misconduct, malicious or reckless misconduct.”

Their response adds that “Strasser and Fitzgerald share no more blame, and likely less, than do the prosecutor, the defense attorney, the judge, the jury and the court of appeals.”

“This suit invites the Court to journey back almost four decades to reenact who should have done or believed what when the murder first occurred, a wholly futile, if not impossible, endeavor for reasons that surpass statute of limitations accrual,” their lawyers wrote.

For his part, Davis said he forgives Dahl. “Honestly, I have never, ever had any ill will,” he said. “I know she was manipulated, and obviously at that point in her life she was malleable.”

But few except her sons and youngest sister remembered that Dahl also died a wrongly convicted killer.

Jarred Lange was 3 and Nick Lange was 8 when police ripped their mother from their lives. Jarred recalls they were playing with neighboring kids on a swing set near their apartment in Eugene, Ore., when their mother told them people were coming to take her away.

Their grandfather drove over in his van, and the boys waited in the back while police cars arrived. Dahl was handcuffed.

“And she got in the car and left,” Jarred said. “And nobody really explained to me a whole lot of things.”

The arrest disrupted everything in their lives. They were shunted from relative to relative for years. Eventually, the boys were sent to Tacoma to live with Jean Dahl, Connie’s youngest sister, who was only 21 at the time.

“She missed her mom’s funeral because she was in jail,” Jarred said of his mother. “That’s something that haunted her forever.”

When Dahl finally walked out of the decrepit El Dorado County jail in 2006, her blond hair and wild humor were gone. Overweight, exhausted and angry, she hitchhiked to Oregon, then bummed a ride to Washington to reclaim her children.

The first thing they did, recalled Nick, was head to McDonald’s. It was a moment of relief after years of pain. But it was short-lived.

Dahl took the boys back to Oregon and for a time lived with her father in his apartment. She had dreamed of owning a food truck that sold breakfast burritos and started cooking meals for the boys. She was known for her homemade chicken strips and her lasagna.

But when she had to move from her father’s place, she struggled to find a landlord willing to rent to a convicted felon. Or an employer willing to give her a chance. Jarred has a stack of applications from all the places his mother tried to get a job and can only remember her holding one, cleaning motel rooms.

Nick and Jarred Lange lived in apartment 10 in Creswell, Oregon, following their mother’s release from prison. “She was strong and stubborn. But she had a good heart and meant well,” Nick Lange says. (Isaac Wasserman / For the Times)

“There was a time where she was homeless with the boys,” Jean Dahl said. “Because she didn’t really have a lot of support when she got out. And so, yeah, it was really tough on her.”

The addictions that had plagued others in her family began to rule Dahl’s life. She began dating a man everyone called “Rat,” her kids recall. Rat’s parents let them camp in their backyard, all four crowded into a single tent.

Jarred remembers the cold October rains in that frail shelter, and how grateful he was when the family moved into a dilapidated double-wide trailer when he was in fourth grade and Nick was a high school freshman.

Despite the hardship, despite the addiction, her boys remember their mother as someone with an infinite capacity for love. Both sons remember when she fell for a stray cat she named Wack Job, who would follow her everywhere. Wack Job had babies, and “the next thing I know we had 40” cats living in the trailer, said Nick.

Life with Connie Dahl could be hard, but they knew they were in it together.

“I always knew my mom had a heart of gold,” Nick said. “People did not treat her good, and they didn’t understand why she was the way she was. And they didn’t even try.”

Dahl died in March 2014 of a heart attack as she was riding her bike to a hotel room Nick had rented for her. He was the only member of the family working at the time, and had wanted to treat her to a hot shower. She was 48.

It was not until a Times reporter sat down with the Dahl brothers in April 2023 that they learned the full story of their mother’s ordeal, and that authorities no longer believed in her guilt.

Sitting in the back of a Barnes & Noble cafe in Eugene, the young men recounted the animosity and friction that still defined their family when it came to their mom. Many of their relatives had shunned her, and by extension, her children.

“Done. Trash. She did it,” is how Nick remembered his mom being treated. Days earlier, Nick had become a father of twin boys. The idea of reclaiming her innocence suddenly had new meaning.

On Friday, in the same courthouse where Dahl was convicted and nearly 39 years after Hylton was killed, that finally happened. The Lange brothers flew in from Oregon and for the first time met Davis, who rode to the hearing on his red Harley-Davidson, a pink tie his nod to the formality of the occasion.

The Lange brothers sat stoically in the front row as Judge Larry E. Hayes formally declared their mother innocent. Hayes and Pierson both apologized on behalf of the state of California.

Outside, under the bright summer sun, the brothers stood on the town’s main street where their mother had likely walked in better days. Their journey was bittersweet, closure but not justice.

“I want people to know that my mom was a good person; she just had a troubled past and made bad choices,” Nick said. “This is long overdue.”

More to Read

About this story

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.