Don’t call Odilia Romero Latina, or Mexican, or Hispanic. She is Zapotec, born in the town of San Bartolomé Zoogocho in the highlands of Oaxaca.

And in the Zapotec language there’s a word she seeks to embody: gozona, the honorable commitment of giving back to your community. Her mission has been making sure Indigenous people are not stifled or stereotyped.

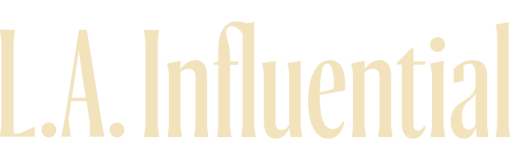

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Disruptors. They include Mattel’s miracle maker, a modern Babe Ruth, a vendor avenger and more. All are agitators looking to rewrite the rules of influence and governance. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

“The labels are still there, but I still refuse to fit into them,” Romero said. “Labeling us is very dangerous because you cannot fit our 500 years of resistance as Indigenous people in one block.”

Romero, 53, left her hometown — “the best place in the world,” where her grandmothers grew their food and drank from rivers — for Los Angeles at 10 years old. Soon after, she recalls, she first encountered racism: A Latina woman called her an “uneducated Indian.”

That kind of racism has never abated. In 2022, an audio leak revealed anti-Indigenous sentiments among some Mexican American members of the L.A. City Council. (Romero was among those who called for their resignations. Council President Nury Martinez stepped down.)

So Romero has spent decades advocating for interpretation to be seen as a human right and visibility of Indigenous people across the U.S., starting in Los Angeles, home to one of the largest populations of Indigenous people in the country.

‘It’s not one person that does all the work. It’s collective work.’

— Odilia Romero

In 2016 she co-founded CIELO, which translates from Spanish to Indigenous Communities in Leadership, with her daughter, Janet Martinez. The L.A.-based group provides Indigenous-language interpretation in 24 states, conducts cultural awareness training for police and helps Indigenous residents navigate institutions — such as courts and hospitals — where language barriers can have big consequences.

During the pandemic, Romero led the effort to translate COVID safety precautions and vaccination efforts into languages such as Akateko, K’iche’ and Q’anjob’al, making life-saving information accessible. And CIELO helped keep immigrant families afloat, distributing millions of dollars to those who had lost income.

Her people are everywhere, she says, laboring unseen in restaurants and bars. They are business owners and students. Last September, Romero attended a festival in L.A. honoring San Bartolomé Apóstol, her hometown’s saint. Hundreds of people were there. She had a relationship with almost every one.

If you ask about her victories, she will insist she can’t take credit alone. It is gozona.

“It’s not one person that does all the work. It’s collective work,” she said. “Without Indigenous communities, without the migrants … we would not exist.”