The mayor of Los Angeles was exhausted.

It was just after 8 p.m. on a relatively ordinary Thursday in November, meaning Karen Bass had talked virtually with Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Mass.), dropped in on an elder turning 100, met with a group of nonprofit leaders in Inglewood, participated in Metro’s Executive Management Committee and brought City Atty. Hydee Feldstein Soto with her to a Latino Leaders Network luncheon.

She had also led an extremely difficult meeting with local Muslim leaders at City Hall, some of whom had lost scores of family members in Gaza, checked in on repairs at the still-shuttered 10 Freeway, held a news conference with California Gov. Gavin Newsom, changed her jacket and shoes several times in the car, given a fireside chat at a fancy evening fundraiser and was now in a black SUV, finally heading home toward Getty House.

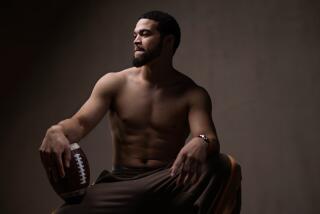

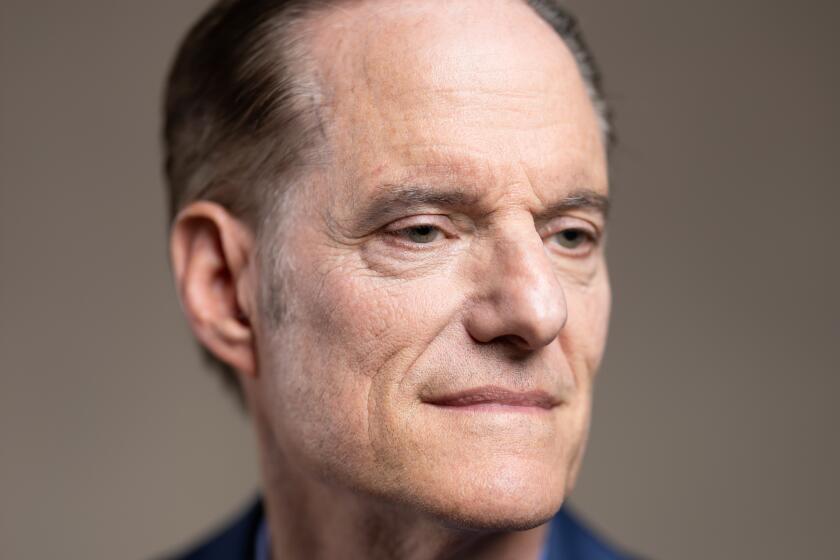

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Disruptors. They include Mattel’s miracle maker, a modern Babe Ruth, a vendor avenger and more. All are agitators looking to rewrite the rules of influence and governance. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

A member of her LAPD security detail was piloting the hulking car through stop-and-go Koreatown traffic. From the back row, the head of Bass’ communications team, Zach Seidl, asked if she’d like to review an upcoming press release, but Bass flatly declined.

“We have to start talking about the one-year because we’ve spent all of our time dealing with the crisis,” Bass told Seidl, referring to the fire that had done serious damage to the heavily trafficked freeway, and her one-year anniversary in office, which was less than a month away.

She yawned, looked down at a message on one of her two phones and sighed, saying there had been a shooting in South L.A.

“My God,” she murmured, as she scrolled further.

Her mood lifted visibly when the phone rang.

“Hey, is there any food? Did you guys cook?” she asked her adult stepdaughter Yvette Lechuga. “Is there any frozen spaghetti that you can thaw out for me?”

There did not appear to be any frozen spaghetti, though there was talk of what remnants might be in another refrigerator. Suddenly, the car slowed at the sight of flashing police lights and fire trucks up ahead on Wilshire, then stopped in front of the commotion at Bass’ urging.

‘People don’t know what to do with collaborative leadership. Their first instinct is to correct me, or to think that it’s weak.’

— Karen Bass

She rolled down her window, instantly hyperalert, composed and commanding. Bass stuck an outstretched hand out the window to greet a uniformed police officer and receive an impromptu briefing.

Among the emergencies that unfold every day across the city’s 502 square miles, this one was relatively small potatoes: a suspicious package, a hazmat team and an all-clear likely to be declared any minute.

So the SUV rolled on toward the Windsor Square mayoral manse, where Bass lives with Lechuga and Lechuga’s husband; the mayor’s 9-year-old grandson, Henry; an infant grandbaby and a rescue German shepherd named Stax.

Bass is now well into her history-making term as Los Angeles’ first female and second Black mayor.

She took office in December 2022, during a bleak moment, with Los Angeles still stumbling out of the wreckage of a racist audio scandal that had put klieg lights on dysfunction at City Hall.

Confidence in local government was at a nadir and disruption was high, with five new council members, a new city attorney and a new city controller all taking their seats simultaneously.

A pragmatic leader, Bass restored a modicum of order to City Hall, building unusually strong relationships with council members and largely making good on a campaign pledge to push a fractious patchwork of government actors toward something resembling coordination.

That’s no small feat in a city where the institutional gridlock can rival that of the freeway system, and particularly impressive given the fact that Bass — unlike her recent mayoral predecessors — had no prior experience in the building.

That’s not to say that Bass is universally liked: She has drawn criticism from left-wing activists unhappy with her signature program to move unhoused Angelenos indoors, as well as from homeowners who don’t think the program is doing enough, among other issues. Her plan to rebuild the depleted ranks of the Los Angeles Police Department also attracted ire from some on the left, though the city has fallen short of those hiring goals.

But her overall success in stabilizing City Hall underscores Bass’ abilities to build coalitions and find consensus where neither seem possible.

It is a skill she has honed during a decades-long professional life that took her from county emergency rooms as a nurse and physician’s assistant, into the trenches of community organizing and, ultimately, on to electoral politics. Bass, who was 51 when she first joined the California Legislature, ascended quickly through its ranks and within a few years became the first Black woman in the country to lead a state legislative body.

Still, deep challenges lie ahead, with the city facing a worsening financial picture in the next year. Last month, the City Council approved Bass’ $12.8-billion city budget, which cuts 1,700 vacant positions at myriad city agencies.

Bass commands respect with an outstretched hand instead of a clenched fist.

During a long mayoral campaign in which her opponent, businessman Rick Caruso, spent nearly $110 million trying to defeat her, Bass’ critics tried to turn her frequent talk of her leadership skills into a liability, dismissing it as kumbaya pablum and arguing that the city needed a far more forceful change of pace.

But to see Bass as a kumbaya leader — or to mistake her softness for meekness — is to fundamentally misunderstand her.

“People don’t know what to do with collaborative leadership. Their first instinct is to correct me, or to think that it’s weak,” she said in December while sipping a mug of Throat Coat tea on the couch in her City Hall office. “I’m OK with that, because I’ve lived with being underestimated.”

She made the city’s sprawling, brutal homelessness emergency the focal point of her first year in office, and it’s clear that her legacy will inevitably rest on her success chipping away at a crisis that some others have deemed intractable.

Inside Safe — Bass’ signature initiative that has been moving unhoused Angelenos into hotels, motels and other facilities — has brought 2,700 people inside as of last month, according to figures compiled by the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. But finding permanent housing for those same Angelenos has been a far greater obstacle, and about 25% of that total have returned to homelessness.

In January, thousands of volunteers fanned out across the county over three days to conduct LAHSA’s annual homelessness count. Results of the federally mandated point-in-time count are expected in late June, but it’s very possible that the city numbers may show an uptick in homelessness when they are released, illustrating the uphill battle Bass faces even as she makes incremental progress.

“Working on homelessness has been like peeling an onion,” Bass said of the constant overlapping barriers to the work. “And you cry when you peel an onion.”

But the relationships she has built at the state and federal levels, something Bass often touts as one of her most valuable assets, paid dividends in her battle on homelessness.

Take one victory last year: Rules requiring applicants for housing to produce identification and document their homeless status and income created a major barrier to housing people, but were viewed as immovable.

Bass called up “one of my closest friends in D.C.,” then-Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Marcia Fudge, and the seemingly implacable barrier quickly fell away, federal policy shifted with a phone call.

“I think she realizes, maybe more than some executives do, how much more effective her leadership can be by working collaboratively with the council and with other stakeholders,” said Council President Paul Krekorian, who has a standing Tuesday morning meeting with the mayor.

‘I don’t believe the way to show my strength is by fighting. I believe the way to show my strength is by winning.’

— Karen Bass

The mayor, who earned brown belts in tae kwon do and hapkido in her early 20s, has occasionally drawn on that background to describe her leadership style.

One lesson is to “be unexpected,” she said. Another is that a real winner is someone who can avoid a fight by outsmarting an opponent. But elected officials, she finds, are often rewarded for fighting, with it viewed as some sign of strength.

“I don’t believe the way to show my strength is by fighting,” she said dryly, offering a wry smile. “I believe the way to show my strength is by winning.”

Fernando Guerra, a political science professor and director of the Center for the Study of Los Angeles at Loyola Marymount University, gave Bass high marks for her first year in office. With the caveat that she was still at the tail end of her honeymoon period, Guerra praised Bass’ relationships with the council and the L.A. County Board of Supervisors and said she was “doing as good if not better than any other mayor in a big city in America.”

He also noted that her first year in office had been scandal-free and that she’d been extremely visible during the November freeway fire incident, publicly handling the crisis and pushing for a quicker-than-expected resolution. But he cautioned Bass would have been wise to take on another major initiative or two beyond homelessness in her first year, given how difficult progress will be and how much of the homelessness crisis remains beyond her control.

The mayor has evolved through a half-dozen lives in her 70 years — from a leftist activist turned frontline healthcare provider to nonprofit leader and, eventually, a nationally recognized politician, leading the state Assembly, then the Congressional Black Caucus, and finally, the city of Los Angeles.

But those close to her say she has also remained radically the same through the changes of scenery. Her roots as a community organizer and her work as founder of the South Los Angeles nonprofit Community Coalition form the core of who she is, they say.

This was evident before the mayor officially took office, on one of the initial days of her transition period, when she greeted a group of local business leaders in the Tom Bradley banquet room at City Hall. Unlike, say, labor or progressive faith groups or social justice advocates, these were hardly natural allies. In fact, many had endorsed Caruso, either individually or through their organizations.

She’s done a “remarkable job” of bringing people who might not have voted for her or be naturally supportive into the fold, USC Equity Research Institute director Manuel Pastor said, citing the Venice homeowners who’ve praised Inside Safe because they’ve been able, “from their point of view, to reclaim their neighborhood.”

But her background also lends another capability: It gives her credibility on the left when people are frustrated by the pace of change, according to Pastor.

“I think she’s gotten more grace than other political figures might get,” Pastor said. The social movement scholar served on Bass’ transition team and has been friendly with her since her activist days.

Those unique relationships were evident last year, when Bass arrived in Leimert Park for an April meeting with Black Lives Matter Los Angeles and other grassroots groups. It was a chilly spring night in the middle of a heated budget process and Bass had taken the symbolic step of meeting the groups on their turf, in a cavernous community space that once housed a weapons dealer.

‘I think she’s gotten more grace than other political figures might get.’

— Manuel Pastor, director of the USC Equity Research Institute

Such a meeting would have been unthinkable during Eric Garcetti’s time as mayor, unless it was conducted over a bullhorn outside the mayoral residence, where BLM L.A. frequently protested.

Some in the room, including BLM L.A. leader Melina Abdullah, had also publicly protested Bass. But the tenor was markedly different. The two women have known each other for decades, and in this more private setting, they embraced in a bear hug.

And Leimert Park also doubles as Bass’ home turf: the heart of Black L.A. was in her congressional district and somewhere she had long organized.

What followed was a lengthy dialogue that remained courteous despite gaping disagreements over how much of the city’s budget should go toward police spending.

Bass listened, took copious notes and never pandered, bluntly acknowledging the points of disagreement.

“Well,” Abdullah told a fellow organizer, stacking chairs in the near-empty room at the end of the night, “we can’t say she runs from us.”