In Jenni Rivera’s rise from Long Beach teen mother to icon of regional Mexican music, family was a constant. She titled her first album Somos Rivera — We are Rivera. It was released in 1992 on a label her parents started in their garage.

Her five children were the center of her life on stage and off. Their antics and affection on the reality show “I Love Jenni,” broadcast on Telemundo’s Mun2 channel, had the vibe of Spanglish-speaking Kardashians.

Nearly a dozen years after Rivera perished in a plane crash in Mexico, her tracks about wild nights, strong women and heartbreaking men remain popular. But the relatives who accompanied her on the journey to superstardom are now waging familial warfare.

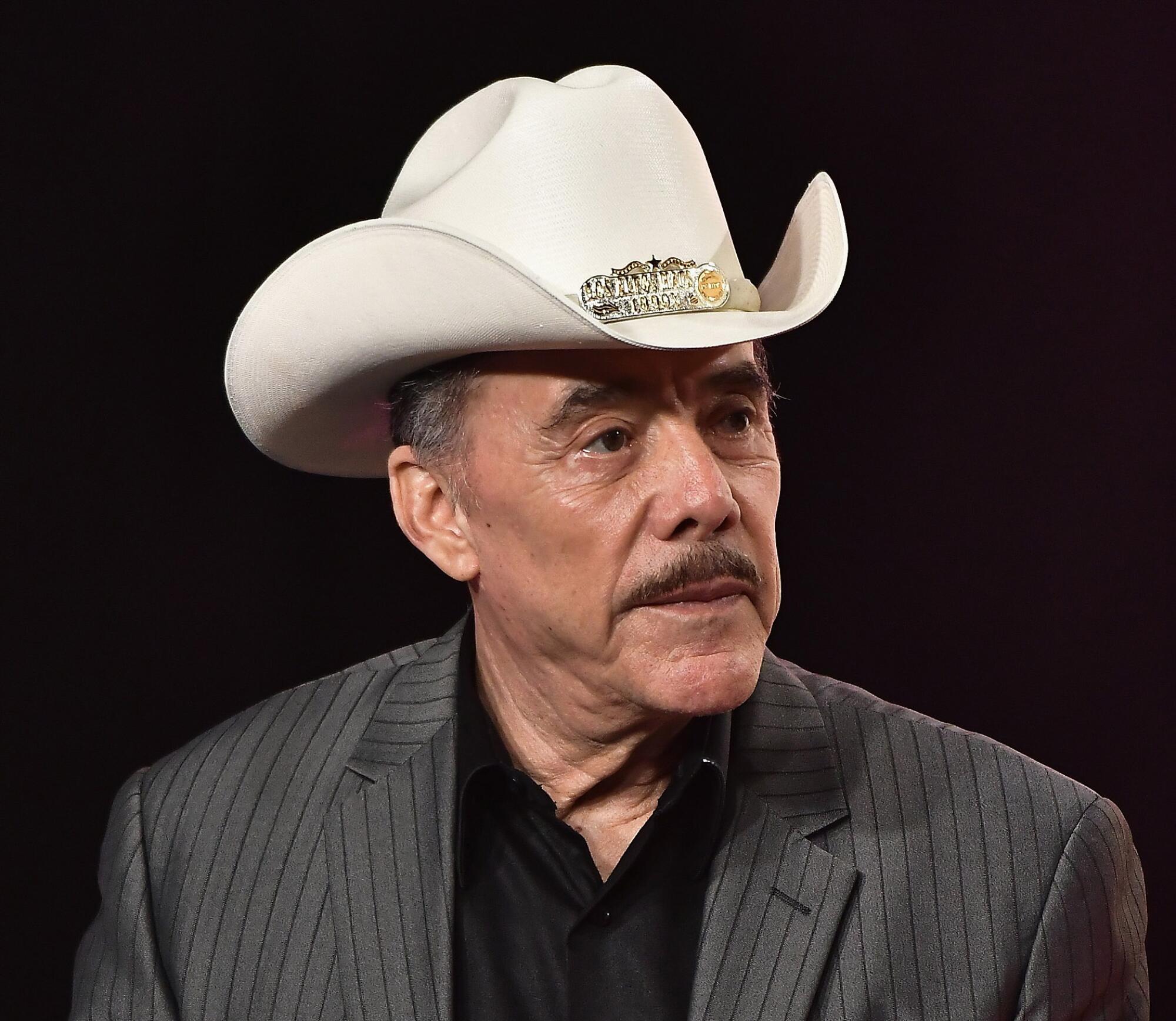

Her children have accused their grandfather, Pedro, a Latin music legend in his own right, and an aunt and uncle of misappropriating part of their inheritance. They have alleged the trio plotted to siphon off funds from Rivera’s estate, once estimated at $28 million, in a decade-long scheme they say preyed upon their grief and industry inexperience.

“This matter provides a perfect illustration of the significant and lasting impact that money, power, and greed can have on a family,” the children’s attorneys wrote last year in a federal lawsuit against companies controlled by their grandfather.

Pedro has denied wrongdoing by him or his children. His attorney blasted the younger generation in a February court filing as having “despicably tossed aside their own grandfather.” Their decision to air the family’s laundry in court, the lawyer wrote, “will exist forever as a stain on the legacy of Jenni and the Rivera family.”

Jenni Rivera is set to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, 12 years after her death in a plane crash. Her legacy in the musica Mexicana genre lives on.

Tales of families battling over the estates of dead celebrities are common in Hollywood. Think Michael Jackson, Jimi Hendrix, James Brown. But the Rivera clash stands apart because it’s playing out within a family — and a culture — that has held blood relations as sacred.

Fans who saw themselves in Rivera’s story of struggle and sacrifice have attacked her children on social media as “mezquinos y sin corazon” — petty and heartless — and “egoístas,” selfish.

“They knew they were going to be called all kinds of names,” said Laura Lucio, Rivera’s longtime friend and producer. “This is the Latino community, where grandpas and grandmas are respected and whatever they say goes.”

Rivera died on Dec. 9, 2012, at the age of 43 as she and her entourage flew from a concert in Monterrey, Mexico, to a television taping near Mexico City. The Learjet plummeted more than 28,000 feet and crashed into mountainous terrain, killing all seven aboard.

At the time, Rivera’s children ranged from 11 to 27 years old. Her eldest, Janney Marin, known as Chiquis, had long been her heir apparent. Rivera gave birth to Chiquis at 15, and they often seemed more like friends than mother and daughter.

But in a twist worthy of a telenovela, Rivera disinherited Chiquis just two months before her death. The singer suspected her daughter of having an affair with her third husband, former Major League Baseball all-star pitcher Esteban Loaiza, after reviewing security footage that supposedly showed them alone in a walk-in closet for 39 minutes. Chiquis denied any liaison.

As a result of their rift, Rivera left everything to her four younger children and named her then-31-year-old sister Rosie, who had worked as an insurance adjuster, to run her estate. To aid her, Rosie tapped their brother Juan, a 34-year-old singer and aspiring producer who had struggled with addiction for years.

“We’re talking about two people who had no real business experience, so it was like training rookies for an impending professional game,” recalled Rivera’s onetime manager, Pete Salgado, in a 2017 book, “Her Name Was Dolores,” one of a half dozen memoirs published by family and friends after Rivera’s death.

The siblings were steering an estate that was worth between $28 million and $30 million at the time of her death, according to Lucio, Rivera’s friend and producer. Over the years, the singer’s empire has included TV programs, a fashion line, radio show, fragrances, beauty products, real estate, a tequila enterprise and, of course, music.

Rivera had released more than 20 albums and sold at least 15 million records during her career. In death, she continues to draw fans. More than 11 years after the crash, her music still attracts 4.8 million monthly listeners on Spotify.

Her second-oldest child, Jacquelin Campos, known as Jacqie, was 23 at the time of her mother’s death. Jacqie was given a job with the estate, but she and her siblings have suggested she had no real power. In their federal lawsuit, the children allege that their grandfather, aunt and uncle discouraged their involvement in the business, telling them “to focus on building their own lives.”

They were reeling in the years after their mother’s death. Chiquis and Trinidad, then 21 and known as Mikey, contemplated suicide, according to declarations filed in the estate’s lawsuit against the owner of the plane and other entities. Jenicka, who was 15, left her public high school to avoid classmates’ stares and pity.

“[E]veryone knew me as Jenni Rivera’s daughter and knew how emotionally distraught I was,” Jenicka wrote in her 2017 declaration. “I was uncomfortable there and didn’t want anyone to see the pain I was going through.”

Then there was the baby of the family, Juan Angel Lopez, known as Johnny, just 11 at the time of his mother’s death. He was particularly close to Rivera, who called him “my little soldier” and liked to say he had a savviness that dated back to the womb.

She sought an abortion when she became pregnant with him in 2000, but a doctor could not initially locate the fetus, she said in her memoir, “Unbreakable,” and on the “I Love Jenni” show. On a second visit, the doctor found it, but Rivera decided to have the child, recalling on the show, “This is going to be a special boy, he doesn’t want to die.”

As a child, he had a sharp mind, finishing high school in two years. He also had a clear interest in the music business. Lucio recalled him asking his mother when he was in elementary school to explain the different jobs in the studio and who got what cut of the profits.

Publicly, the family rallied around Johnny after his mother’s death. Pedro referred to the boy as “the most affected” by her loss in a 2018 declaration in the plane litigation. But privately, his aunt, uncle and grandfather were plotting against Johnny and his siblings, according to their suit.

An employee at Pedro’s record label, Cintas Acuario, told the children years later that she overheard the trio hatching a plan about a month after Rivera’s death to steal from the estate by funneling money to the label. Rivera’s brother told Rosie and Pedro they could get away with it because most of the kids were “stupid children” with no grounding in the business, the suit claims.

“The only one of the beneficiaries who would ever be capable of catching on was … Johnny,” the suit quotes Juan as saying. He “specifically referred to Johnny as a ‘cabrón’” — sometimes translated as bastard — “who the perpetrators of the scheme would have to be cautious of in the future.”

The older Riveras deny the conversation ever occurred and accuse the employee, Fabiola Avalos, of making up the story after she lost a sexual harassment case against Pedro. Avalos confirmed to The Times that she overheard the conversation, but declined further comment.

Juan said in an interview that he was flabbergasted by the allegation, saying, “Where did I go so wrong as a human that they could believe that from me?”

If there were concerns Johnny might cause problems for his aunt, uncle and grandfather, they were prescient. At age 16, the boy started asking for a financial accounting of his portion of the estate. Chiquis, who was his guardian, told him to wait, recalling in “Unstoppable,” one of two memoirs she has published, “I didn’t think it was a good idea to upset the family.”

He asked again at 18, Chiquis wrote, and was again told no. When he was 20, she wrote, “he brought it up again and I asked him to sit on it and pray. He did and was resolute with his decision…”

Johnny’s persistence set the stage for a showdown between two very different branches of la familia Rivera.

As her star rose, Rivera was able to give her children a comfortable life, first in a Corona mansion and then in a four-acre Encino estate later sold to television personalities Vanessa and Nick Lachey.

It was a far more luxe upbringing than she and her five siblings had. Her parents emigrated from Sonora in the 1960s. Her father picked grapes in the Central Valley for a time. The family bounced around L.A., dodging evictions, until finally buying a two-bedroom home on Gale Avenue in a part of Long Beach then plagued with gangs.

The Riveras loved corridos, a genre of Mexican ballads about drug trafficking, government corruption and other gritty topics, and sold CDs and cassettes at the Paramount swap meet before launching Cintas Acuario in the late 1980s.

The label’s marquee act initially was the pioneering Mexican singer-songwriter Chalino Sanchez and later Rivera’s younger brother Lupillo. The intense focus on her sibling frustrated Rivera, who recalled in her memoir how she drove her cassettes from one Spanish-language radio station to another trying to get airplay.

She was 30 with four kids and a real estate job in Compton before she had her first hit, “Las Malandrinas,” a brass-heavy corrido with an unconventional subject, hard-drinking, rule-breaking women.

In the decade that followed, her career exploded, eclipsing Lupillo and other Cintas acts. She racked up accomplishments, from selling out venues such as the since-demolished Gibson Amphitheater and Staples Center to starring in a popular cable show and inking a sitcom deal with ABC.

It was an adjustment for her father, who called himself “El Patriarca del Corrido” — “The Patriarch of Corridos” — but had limited experience with mainstream success. Lucio recalled that, long after Rivera made it big, Pedro was still showing up in the parking lot of her concerts to sell cassettes and CDs from the trunk of his car.

Her family leaned on her for money as her star rose. After her parents’ marriage faltered in 2007, she supported her mother, Rosa, and poured money into their struggling record label. Rivera eventually owned 50% of Cintas, her mother wrote in 2010 divorce papers. Her father acknowledged in a filing the same year a $100,000 loan from their daughter to run the business. She gave to other relatives too.

“There were circumstances where she felt frustrated because she felt regardless of how much she gave them, it was never enough, and she wasn’t appreciated,” Lucio said. Lucio and the estate became enmeshed in litigation over work she did writing the singer’s memoir. They reached a settlement in 2015 before trial.

Rivera became increasingly bitter about the handouts, according to Chiquis, who in her memoir recalled her mother saying the year before her death, “All I am to my family is money.”

Her passing was an emotional blow to her parents and siblings, but also a potential windfall. Her former manager, Salgado, who died in 2020, recalled in his book that her family started discussing plans for a 52-date show called “the Rivera Dynasty Tour” before the singer’s body had even been returned from Mexico.

“I honestly thought I would find a family in mourning, torn and heartbroken by this tragedy, lost and overwhelmed by the circumstances,” Salgado wrote in his memoir of a meeting a few days after the plane crash. “Instead, I found a family trying to figure out how to make their next buck.”

Juan called the account a lie. Rivera’s sister Rosie and her father, Pedro, did not respond to requests for interviews relayed through their lawyer. Rosie wrote in a 2016 memoir, “My Broken Pieces,” that in managing her sister’s affairs, the children were “my number one priority.”

In an interview, Juan said Rosie ran the estate so frugally that she almost fired a nanny who treated herself to an energy drink on the family dime, telling the woman Rivera “did not die so you could buy yourself Red Bulls.”

In another business, in another family, the audit Johnny demanded might have played out in secret. But this was the Riveras.

Jenni Rivera was famous for making her private life public, singing and speaking about single motherhood, domestic violence, weight battles and infidelity. Her survivors picked up her mantle and spilled out their feud on social media.

“He is waiting for more money to continue spending,” Johnny’s grandmother, Rosa, chided on YouTube in June 2021. She added of her grandchildren, “They haven’t worked as they should, the ones who have worked are my children, Rosie and Juan.”

Rosie wept uncontrollably in her own YouTube video, saying, “The kids know I didn’t steal and that makes it worse.”

Chiquis revealed on Instagram in January 2022 — she currently has nearly 6 million followers — that “someone really close to Rosie” had made off with around $80,000 from the estate. (Rosie acknowledged to a Mexican morning show that, years earlier, her husband took money to feed a gambling problem and she repaid it.)

Around that time, Rosie announced she was handing over control of the estate to her niece Jacqie, Rivera’s second child and Johnny’s sister. A news release suggested a peaceful transfer, stating that the audit had turned up “no evidence of any crime, misappropriation or theft of fiduciary funds by Rosie.”

The children’s lawyer would subsequently say in court that the pleasant tone was just a way to free an estate that “was essentially being held captive” by Rosie and Juan.

Their questions about the financial management remained, so the children dispatched Jacqie to get answers from their grandfather. What happened at the meeting depends on whom you ask.

Pedro asked Jacqie “for a plan, a strategy of what they wanted to do,” Juan said in an interview. “She told him she’d get back to him within a week with a breakdown.”

Juan said she never did.

Lucio, Rivera’s friend and producer, said in an interview that she has talked with the children and they told her Pedro refused to answer questions about estate business.

“He was not helpful,” Lucio said. She said Jacqie told her siblings, “We’re gonna have to file a lawsuit because we’re not getting straight answers.”

The lawsuit brought in September by the children on behalf of Rivera’s estate accused Cintas Acuario and another company controlled by Pedro of copyright infringement, trademark violations, breach of contract, fraudulent concealment and other claims. It demanded an accounting and an unspecified amount of money.

The suit noted that Cintas had not regularly paid royalties or complied with contracts that required quarterly accounting statements to the children. John Begakis, a lawyer for Pedro’s companies, confirmed that royalties were not paid for a decade, but asserted in an interview that it was because the labels had discovered Rivera had been overpaid in previous years and was trying to recoup that money. He wrote in a court filing this spring that the estate still owes about $775,000 to one of Pedro’s companies.

Rivera still looms large in L.A. She is set to receive a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame later this month. People continue to pose for photos at murals dedicated to her. One at Jenni Rivera Memorial Park in Long Beach recaps her struggles: “She was expected to fail and give up. She persevered and fought for her children.”

At Coachella in April, the megastar Peso Pluma paid tribute to the Mexican music icons who came before him. Rivera was one of them. As her face flashed onto a screen on the stage, her son Johnny, who was in the audience, hooted and screamed, “That’s my mama!”

Court proceedings offered little of that joy. More than a dozen reporters from Spanish language news outlets — including Telemundo and Univision — gathered outside the federal courthouse in February, awaiting the outcome of a motion to dismiss the case.

A bailiff checked to make sure everyone stayed off their phones, an adjustment for the terminally online Rivera family gathered inside. Rivera’s children, some dressed in black, squeezed together on a bench in the packed courtroom. Across the aisle, their uncle Juan fidgeted in his seat.

The attorney for Pedro’s companies tried unsuccessfully to persuade a judge to dismiss the case, saying the children had waited too long to complain about the lack of royalty payments and statements.

“They’ve sat back and have not been paying attention,” Begakis said.

As U.S. District Judge Stanley Blumenfeld Jr. referenced the allegations of an orchestrated effort by blood relatives to conceal violations, Rivera’s daughter Jenicka gave a tight smile. The parties were to begin preparing for trial — one set to unfold next year.

When they exited the courtroom, Rivera’s children veered right, while Juan turned left. Rivera’s brother told the swarm of reporters waiting outside that he felt “nothing” upon seeing his nieces and nephews.

“I believe that family ties no longer count in this case,” said Juan, who wore a baseball cap with a cross that overlaid the word “Chosen.”

As the children exited the courthouse, a ripple of excitement ran through the security line and people began calling out to them.

One woman shouted, “We love you, Jenni.”

More to Read

Subscriber Exclusive Alert

If you're an L.A. Times subscriber, you can sign up to get alerts about early or entirely exclusive content.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.