On the blisteringly cold day of the Iowa GOP caucuses, President Biden’s campaign convened reporters in a conference room to contrast the Democratic incumbent with the Republican field and its front-runner, former President Trump.

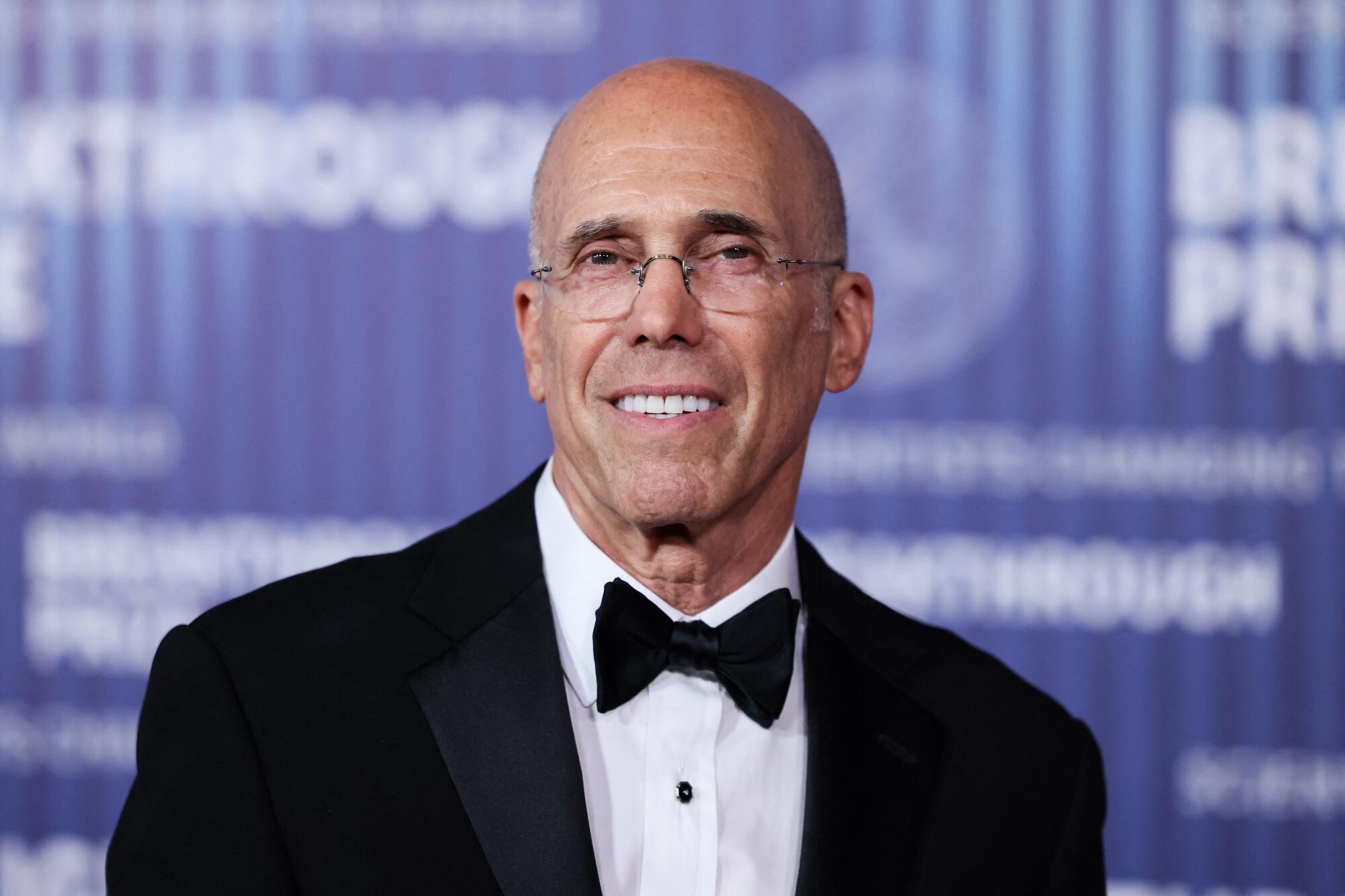

Making the case alongside the governor of Illinois and a senator from Minnesota was Jeffrey Katzenberg, the entertainment industry titan who, until recently, was more likely to be seen on a red carpet in Hollywood than in a drab meeting room in Des Moines.

“Team Biden-Harris is entering the election year with more cash on hand than any Democratic candidate in history at this point in the cycle,” he said at the January gathering, touting the campaign’s $97-million fundraising haul in the fourth quarter of 2023. “We’re entering the election year with the resources, enthusiasm and energy needed to mobilize the winning coalition that will reelect Joe Biden and Kamala Harris.”

Politically active since he was a teenager — but often behind the scenes as a top fundraiser — Katzenberg this year is taking on the highest-profile political role he’s ever had, as a co-chair of Biden’s reelection campaign in what will likely be a tough race against Trump.

He’s Biden’s only campaign co-chair who is not an elected official, a sign of how entrenched Katzenberg has become in Democratic politics since his peak as a Hollywood mogul. After decades spent shaping the stories that Americans watch on the silver screen, Katzenberg now spends all of his time — and some of his fortune — influencing politics in Los Angeles, California and the nation.

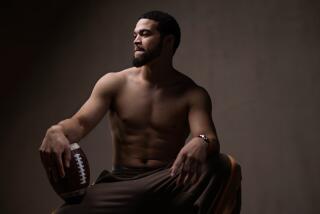

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Disruptors. They include Mattel’s miracle maker, a modern Babe Ruth, a vendor avenger and more. All are agitators looking to rewrite the rules of influence and governance. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

Katzenberg was a chief architect of the major Biden fundraiser on Saturday at the Peacock Theater in downtown Los Angeles that included a conversation between the president and former President Obama moderated by late-night TV host Jimmy Kimmel, and also featured appearances by actors George Clooney and Julia Roberts.

He shaped the leadership of Los Angeles in the last election cycle by urging Karen Bass to run for mayor, giving $1.85 million to an independent campaign to help elect her and pouring $1 million into the effort to oust former Sheriff Alex Villanueva — making him the biggest individual spender in L.A. city and county elections in 2022 outside of anyone running for office. The year before, he gave $500,000 to help Gov. Gavin Newsom beat back an attempted recall.

Newsom, a prominent Biden supporter who talks with Katzenberg about homelessness and other problems California grapples with, described him as “hard-wired for excellence” and a “competitive son of a bitch” who focuses on building meaningful connections.

“That’s the difference with this guy,” Newsom said. “A lot of successful people are transactional. This guy is building relationships that last.”

Katzenberg and his wife, Marilyn, have donated more than $30 million to candidates, state parties and causes since 1989, according to an analysis conducted for The Times by the nonpartisan group Open Secrets, which tracks electoral finances.

It’s not as much as Democrat George Soros or the late Republican Sheldon Adelson have poured into their favored political causes. But Katzenberg is just as coveted because of his prowess at extracting enormous donations from wealthy power brokers — and signaling whom they should back.

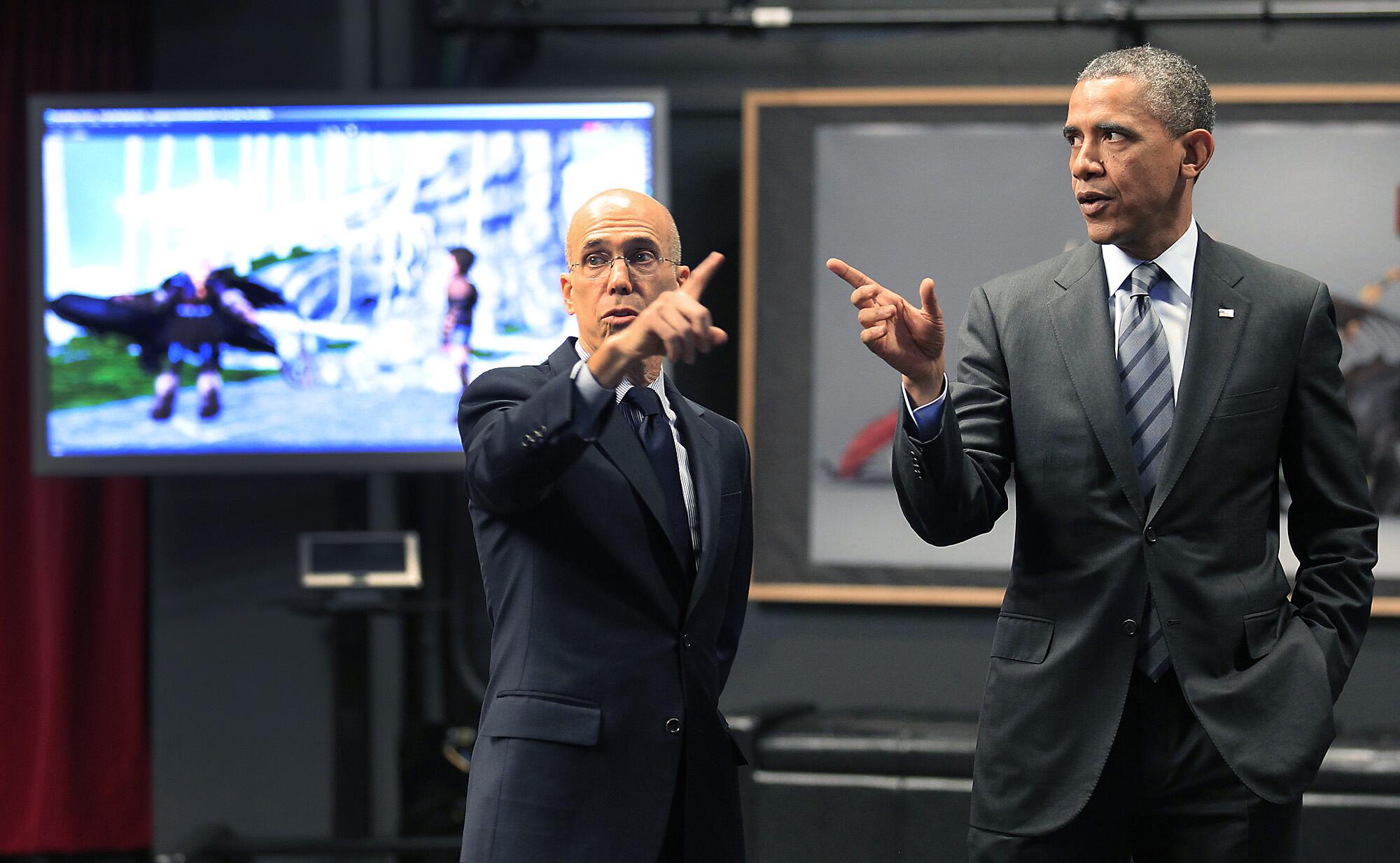

His decision to back Obama over Hillary Clinton, the favorite of the Democratic establishment, was a pivotal moment in the 2008 presidential campaign.

In 2012, Katzenberg co-hosted the biggest presidential fundraiser in history at that point, amassing $15 million for then-President Obama’s reelection bid. Wolfgang Puck catered the star-studded dinner, held under a tent on the basketball court at Clooney’s house.

In December, Katzenberg was instrumental in organizing a Hollywood soiree for Biden’s reelection bid, a gathering where top tickets approached $930,000 per person. Musician Lenny Kravitz performed and co-hosts included showbiz legends Steven Spielberg, Rob Reiner and Shonda Rhimes.

Katzenberg declined to comment for this article. Numerous sources told The Times that he has become a regular presence at the White House, routinely talking to the president and his top aides on the phone, by text and during occasional visits.

Biden campaign manager Julie Chávez Rodríguez, a Californian who is the granddaughter of legendary labor leader César Chávez, said she speaks with Katzenberg multiple times a week — not only about raising money, but also about what the campaign can do to connect with voters.

“He definitely does enjoy getting in the weeds, especially … the new technologies that are coming up that we should dig into, what are the new platforms or even new personalities and influencers,” Chávez Rodríguez said.

‘Here’s why I think the three presidents who I’ve known turned to him for close advice: He gives you good advice, he doesn’t pull any punches and, of course, he raised money.’

— Paul Begala, Democratic strategist on Jeffrey Katzenberg

Republicans said Katzenberg’s role with the campaign illustrates that Democrats are out of touch with most Americans.

“It’s ludicrous to think a coastal elite, Hollywood multimillionaire can help Biden connect with the millions of Americans who are struggling under the weight of Bidenflation, concerned with the crisis at the southern border, frustrated by the brazen crime in their communities, or fed up with sending their children to failing schools — all issues that have become staples of the disastrous Biden administration,” said Jessica Millan Patterson, chair of the California Republican Party.

It’s criticism Katzenberg has heard before. At the Iowa press conference, Katzenberg bristled when a reporter asked whether his presence underscored GOP claims that Democrats had become a party of coastal elites who do not understand the working class.

“Not. At. All,” he responded. “President Biden was elected by a greater majority than any president in the history of our country, 8 million votes, and for you to suggest that that was a divided vote of Los Angeles and the East Coast is just factually inaccurate.”

Katzenberg, 73, grew up in New York City as the son of a stockbroker and an artist. His first foray into politics was at age 14, when he volunteered on the successful 1965 mayoral campaign of John Lindsay, a Republican who had the support of the Liberal Party of New York. He moved to Hollywood in the 1970s, eventually becoming chairman of Walt Disney Studios in 1984.

Developing a reputation as a frenzied, prickly, micromanaging chieftain who wakes up early every morning for intense workouts, Katzenberg turned an organization once ranked last at the box office among the major studios into the industry’s top performer with animated blockbusters such as “The Little Mermaid” and “The Lion King.”

Katzenberg left Disney in 1994 amid reported tensions with Roy Disney, Walt’s nephew, and Chief Executive Michael Eisner. He sued the Disney Co. for breach of contract and received a confidential settlement that analysts cited by The Times estimated at $250 million to $275 million.

He founded DreamWorks SKG in 1994 with Spielberg and David Geffen. In 2016, Comcast bought Katzenberg’s DreamWorks Animation studio for $3.8 billion in a deal that gave Katzenberg $390 million but required him to relinquish his role in the company.

His most recent entertainment venture, Quibi, a streaming service that launched early in the COVID-19 pandemic, closed after just seven months.

While working together at DreamWorks, Katzenberg and Spielberg founded a super PAC to support Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign. That earned them each a gift from the PAC’s top advisor: a cowbell inscribed with the words “Bell Cow.”

“That’s the one that all of the other cows listen to and follow. A natural leader,” said Paul Begala, a Texan who was the chief strategist for Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign. Katzenberg “is the one everybody follows. ... He’s brilliant, principled and generous.”

The super PAC wound up spending $65 million in the presidential race — including at least $4.1 million donated by Katzenberg — an effort that was pivotal to Obama’s reelection.

It’s the kind of support that has helped make Katzenberg a confidant to Biden, Obama and Clinton, Begala said.

“Here’s why I think the three presidents who I’ve known turned to him for close advice: He gives you good advice, he doesn’t pull any punches and, of course, he raised money,” Begala said. “Even more than that, it’s what he doesn’t do. Jeffrey never leaks, he never lies and he never asks for anything.”

In 2021, as California began to reopen from pandemic-induced closures, Katzenberg started meeting with Los Angeles city officials about how to address homelessness. At the time, he told The Times that he’d been passionate about the issue for years but that the proliferation of encampments that emerged during the pandemic spurred him to engage local politicians.

“It doesn’t matter what part of the city that you’re in — the travesty of this is undeniable, for all of us,” Katzenberg said in a 2021 interview with The Times.

Villanueva, who was the Los Angeles County sheriff at the time, said he talked with Katzenberg about his concerns about homelessness at a lunch at the Beverly Hills Hotel.

“He seemed interested in who I was supporting for the mayor’s race, and made no mention of the sheriff’s race,” Villanueva said in an email to The Times.

Katzenberg wound up backing Villanueva’s opponent, Robert Luna, by giving $1 million to a committee that made negative ads about Villanueva.

“In hindsight, Katzenberg lacked the courage to tell me what he planned to do with the sheriff’s race, and his involvement assisted Luna in winning in November of 2022,” Villanueva said.

‘A lot of people dabble, a lot of people show interest. There are few people that I have met that show a [greater] level of commitment and understanding than Jeffrey.’

— California Gov. Gavin Newsom

In the run-up to a City Council vote to impose new anti-camping rules that would allow the city to remove some encampments, Katzenberg emphasized to civic leaders the negative impacts that such settlements were having on Los Angeles. His support for the ordinance drew the ire of liberal activists.

It was around that time when Katzenberg met then-Rep. Karen Bass (D-Los Angeles) and encouraged her to run for mayor. In Bass, he saw someone who had values that aligned with his, was competent and could stand out in a large competitive field of candidates.

Bass was working on police-reform legislation when she agreed to meet with Katzenberg and another power broker. She assumed that’s why they requested the meeting.

“When I got on the Zoom, they mentioned the mayor’s race, and I was like, ‘Oh, no, I’m not thinking of that at all,’” Bass said in an interview.

Katzenberg was one of a chorus of voices, including Black leaders in South L.A. and labor movement bigwigs, who tried to coax Bass into the race in the spring of 2021. She entered after her close friend, former Councilman Mark Ridley-Thomas, announced he wouldn’t run — and with Katzenberg in her corner prepared to spend what it would take to help elect her.

Through the years, Katzenberg has talked with local and state officials about homelessness, but with what Bass describes as a relatively light touch.

“You would think somebody like him — of his wealth and influence — would be someone who would be saying, ‘Well, this is my idea and this is my suggestion.’ He just doesn’t do that,” Bass said.

Katzenberg’s concerns about homelessness factor into his relationship with Newsom as well. The governor, who has known Katzenberg since he was mayor of San Francisco in the 2000s, said they became closer after he was elected governor in 2018.

“A lot of people dabble, a lot of people show interest. There are few people that I have met that show a [greater] level of commitment and understanding than Jeffrey,” Newsom said.

He recalled the first time Katzenberg wanted to talk about homelessness, he flew up to Sacramento during a storm for a half-hour meeting when a Zoom would have sufficed.

After the meeting, the governor immediately called one of his top aides and told him: “Sit down with this guy. … He understood what the hell he was talking about at a granular level.”