On a Thursday in early June, a Border Patrol bus pulled up to a San Diego County transit station and 50 migrants got out.

Immediately, they were bombarded with offers from local vendors:

“Free charging, guys,” said a man with a folding table. “Free pizza.”

“Senorita, welcome, we can exchange your pesos for dollars,” another man said, making his way through the migrants who were by then crowded onto the sidewalk, a wad of cash in his hand.

“Taxi al aeropuerto rapido,” a licensed taxi driver said. “Quick taxi to the airport.”

“SIM card, cigarette,” another man said, speaking through the cigarette perched between his lips.

The chaotic scene had been the norm at the Iris Avenue Transit Center in San Ysidro ever since the county’s migrant welcome center ran out of money and closed in February and Border Patrol resumed dropping off migrants at the station throughout the day. Many of those arriving at the California border have family or friends elsewhere and don’t stay in the area long.

How President Biden’s executive order limiting asylum is playing out on the California-Mexico border.

Al Otro Lado and other nonprofit groups routinely deployed aid workers to lead migrants to the trolley, which they could take to a free airport shuttle two stops away. But as the number of people crossing the border swelled earlier this year, a competing presence had also sprung up: street vendors, licensed and unlicensed taxis who saw in the migrants a business opportunity. Aid workers worried the newcomers were being exploited; taxi rides could go for $100, far above the $35 on Lyft.

Three weeks later, the scene had once again shifted. In the wake of President Biden’s June 4 executive order limiting asylum claims at the southern border, the transit station is usually deserted, said Melissa Shepard, directing attorney at the Immigrant Defenders Law Center, which opposes Biden’s asylum order.

Gone were the street vendors, taxi drivers and migrants, she said.

The shift along the California border means that rural sites east of San Diego, where hundreds of migrants once waited to be processed by Border Patrol agents after illegally crossing from Mexico, are now mostly barren.

Meanwhile, shelters on the Mexican side of the border are reaching capacity, Shepard said.

By the end of June, three weeks after the executive order took effect, the seven-day average of migrant arrests had dropped more than 40% to fewer than 2,400 encounters per day, according to the Department of Homeland Security. The agency said that’s the lowest level of illegal crossings since Biden took office.

President Biden’s action will shield those without legal status who are spouses of U.S. citizens and have lived consecutively in the country for at least 10 years.

Other recent changes are likely to affect the California border. On Monday, the agency announced a deal offering foreign assistance to help Panama deport more migrants far before they can reach the U.S.-Mexico border. And as of this month, Chinese citizens, most of whom reached the U.S. through California, can no longer enter Ecuador without a visa.

Homeland Security officials say they have stepped up removals, with 120 deportation flights to more than 20 countries since the executive order was announced. Last weekend, the agency conducted its first large charter flight to China since 2018.

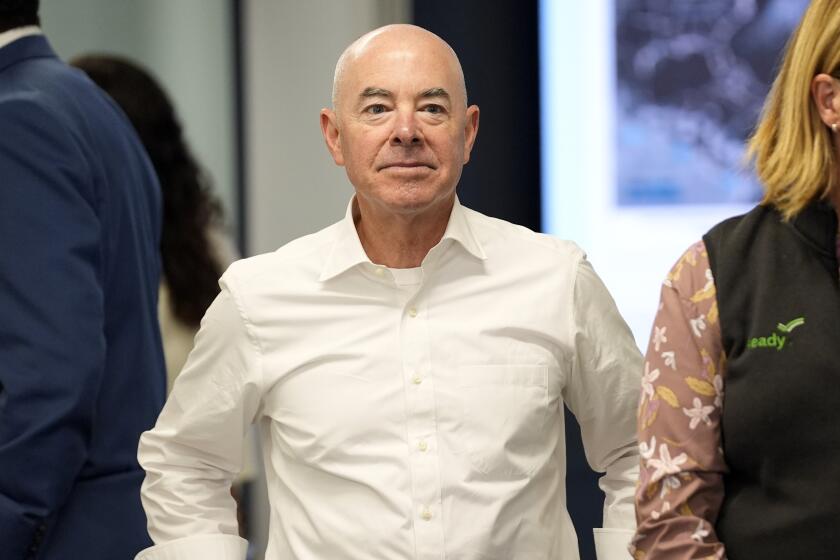

“These actions are changing the calculus for those considering crossing our border,” Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro N. Mayorkas said during a briefing last week in Tucson.

1

2

1. An asylum seeker receives food offered by the American Friends Service Committee as they wait to be detained by border patrol. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times) 2. Inside Movimiento Juventud 2000, a migrant shelter, where dozens of families seeking asylum are living as they wait to meet with US officials. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

Immigrant advocates say that deterrence policies such as Biden’s asylum order can lower crossings for a while, but that the numbers eventually pick back up because the conditions people are fleeing haven’t changed. They say the policy will push people into more remote, dangerous areas and lead to more injuries and deaths.

“An average person who’s fleeing their country is not going to say, ‘What are U.S. immigration laws right now?’” Shepard said. “I don’t think any amount of restriction is really going to stop somebody from trying to seek safety.”

Around the same time as Biden’s executive order took effect, Catholic Charities increased shelter capacity for single adults being released in San Diego.

Since then, few people have been released to the transit center, Shepard said. During the last week, she said, migrants have been released there on a single afternoon. If street releases pick back up, the vendors are likely to return, she said.

Meghan Zavala, data and policy analyst at Al Otro Lado, said the vendors created a hostile environment for nonprofit volunteers. Once, she said, an unlicensed taxi driver tried to scare migrants away from an Al Otro Lado volunteer, telling them in Mandarin that aid workers were trying to trick them.

Vendors also encouraged migrants to stick around at the transit center instead of going to San Diego’s Old Town, where they would have more transportation options, or to the airport, where they could connect to free Wi-Fi, contact family or friends and book flights out of the region.

“It’s just very challenging to engage people who speak other languages when the only person in the vicinity who speaks their language is some type of unregistered vendor,” she said.

At the transit station, licensed taxis had an organized system for securing customers: Each arriving driver wrote their vehicle number down on a piece of paper that was secured to a tree.

Ahmed Gadudow, 52, parked his green-and-white taxi behind two others on the sidewalk to wait his turn — sometimes hours later — for a customer.

Gadudow said Chinese migrants would get in only the unlicensed cabs driven by other Chinese people. He charged $75 per airport ride, which he believed was a fair price.

“Some of them don’t care about volunteers,” he said. “They have the money. They just want to go.”

He acknowledged that at times, arguments between licensed and unlicensed taxi drivers had gotten tense.

Advocacy groups have dealt with their own security concerns. Catholic Charities hired armed guards after a right-wing activist posed as a pest inspector, went to a hotel where the organization has a shelter and posted a video online claiming migrants were there, prompting threats to staff. At a shelter in San Diego run by the nonprofit Jewish Family Service, Kate Clark, the organization’s director of immigration services, also described an uptick in security issues this year, mainly protesters who show up to record videos outside the shelter.

Experts said the decline in migrant arrests is likely due to a combination of factors: the executive order, stringent enforcement by the Mexican government and the temperature rising under the hot summer sun. Last year, crossings dropped during the summer and picked up in September, said Pedro Rios, director of the American Friends Service Committee’s U.S./Mexico Border Program.

Rios said numbers are significantly lower at the crossing west of San Ysidro known as Whiskey 8. A few weeks ago Border Patrol was typically picking up 50 or more people at a time; now a handful of people will wait for agents to arrive.

For first time in 25 years, San Diego is the top spot in the nation for migrant border crossings, surpassing Tucson.

But regardless of how many people show up, Rios’ orientation is the same. Migrants who arrive at Whiskey 8 are stuck between two border barriers dividing the U.S. from Mexico. Under a white canopy on the American side, Rios asks whether anyone is hurt and offers them water, instant soup and backpacks.

“You are already in the United States,” he told 10 migrants from Ecuador, Colombia and Guatemala last month, speaking to them between the metal bars. “This is San Ysidro, Calif.”

Rios told the migrants they’d be asked to remove their shoelaces and all but one layer of clothing (two layers for women). After processing, he said, they’d get paperwork with an immigration court date and be released to the transit center, where people would offer to sell them things.

“I recommend you don’t buy anything there,” he said.

Sam Schultz, an aid worker who lives near the border east of San Diego, said he has seen people arriving only at one area just west of Jacumba Hot Springs, where the border barrier is made of salvaged military landing mats.

On Monday, Schultz said, he saw zero migrants. A few days before, he saw around 30, and about a week ago he saw 50. Temperatures have surpassed 100 degrees.

“The change is this: People are still coming in but usually in smaller lots,” he said. “Our major concern right now is making sure nobody’s getting lost and getting dehydrated. It’ll kill you to be out here.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.