Gwynne Shotwell had the unenviable task of selling a rocket that kept crashing.

The year was 2007. Shotwell, then vice president of business development for a fledgling company called SpaceX, was pitching satellite communications firm Iridium on why the veteran player should sign a deal with a company that hadn’t successfully launched any rocket, much less the larger and more complex one it was offering up.

She was so confident her company would deliver that she was willing to negotiate a deal with terms very favorable to Iridium, and less favorable to SpaceX, should anything go wrong.

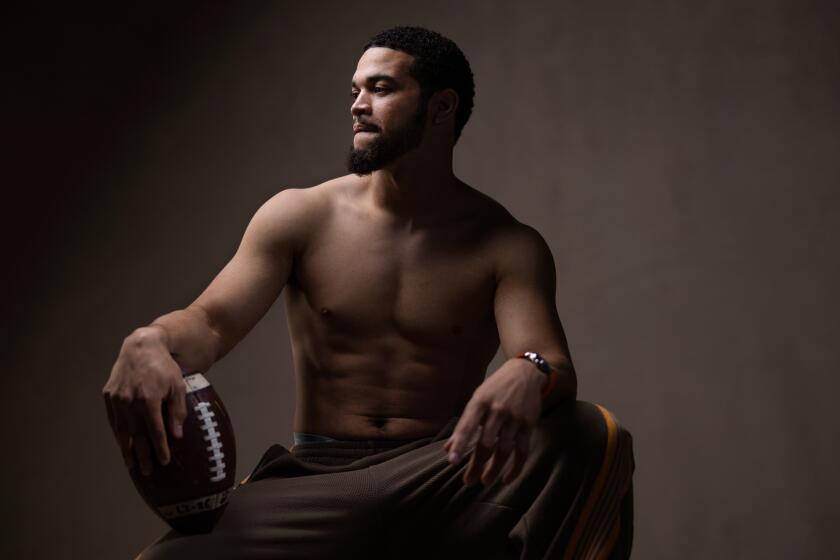

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Disruptors. They include Mattel’s miracle maker, a modern Babe Ruth, a vendor avenger and more. All are agitators looking to rewrite the rules of influence and governance. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

“She was not trying to just sell us something,” said Suzi McBride, Iridium’s chief operations officer. “She believed in it, and she was gonna make it happen and ensure that it was there.”

Billionaire Elon Musk may be the visionary behind SpaceX’s multi-planetary ambitions, but Shotwell, 60, is the steady hand behind the company’s earthly success.

As president and chief operating officer, Shotwell runs the Hawthorne company’s day-to-day operations and manages finances, customer negotiations, human resources and relationships with government entities — in short, all of the people-focused parts of a business that help it thrive.

She’s a rarity at a Musk company — an executive, the second-in-command, no less, who has lasted for more than two decades. More than that, she has Musk’s ear and his trust.

The partnership between the mercurial technologist with the brash personality and penchant for making headlines and the engineer-turned-businessperson who cares little about the public spotlight has driven SpaceX to the highest echelons of the aerospace industry.

The company commands lucrative contracts with the U.S. military, NASA, commercial firms and the European Space Agency. At the same time, it is building a massive Mars rocket and venturing into the broadband internet market with its Starlink satellite network.

In all, the privately-held SpaceX is currently valued at about $210 billion.

“I see Gwynne sometimes like the orchestrator inside the circus ring, who’s spinning the plates and just keeping all of the various different elements in equilibrium,” said Martin Halliwell, former chief technology officer of satellite firm SES who negotiated six contracts personally with Shotwell and now considers her a friend. “Without her, it may have been successful, who knows? We’ll never know. But I think it would have been a lot more abrasive.”

Reared in a Chicago suburb, Shotwell, who declined to be interviewed for this article, was popular and well-rounded, excelling in academics while also playing varsity basketball and cheerleading.

‘I see Gwynne sometimes like the orchestrator inside the circus ring, who’s spinning the plates and just keeping all of the various different elements in equilibrium.’

— Martin Halliwell, former chief technology officer of satellite firm SES

Her mother jump-started her interest in engineering after taking Shotwell to a Society of Women Engineers conference. The panel discussion featured different types of engineers, but Shotwell was immediately drawn to the words of a mechanical engineer, as well as her “beautiful suit [and] fabulous shoes,” according to a 2014 Orange County Register article.

“I thought, ‘OK, engineers can be cool too. I’ll just be a mechanical engineer,’” Shotwell told the alumni magazine of Northwestern University, her alma mater, in 2012 about that fateful encounter. “I never wavered from that decision.”

After graduation, Shotwell went to work at Chrysler and was identified early on as management material. But she balked at being placed in a leadership training program, preferring instead to work on engineering problems. She made the jump to the aerospace industry, worked in thermal analysis for Aerospace Corp. in El Segundo and then transitioned into business development at a small South Bay company called Microcosm.

There, she formed a successful partnership with Hans Koenigsmann, the company’s chief scientist, and together, they set out to sell studies to government and commercial customers.

“We were kind of like a tag team — I was the German, slightly grumpy scientist, and she was the bubbly American businessperson,” said Koenigsmann. “I think we were complementary.”

It was Koenigsmann who would help get Shotwell to SpaceX, suggesting she meet Musk when she dropped him off at the startup’s office after one of their regular lunches. Musk had invested $100 million of his PayPal fortune into the company, a move that gave Koenigsmann confidence that the yet-unproven SpaceX had at least a bit of a runway.

“The job is certainly safe for three to five years,” Koenigsmann remembers telling Shotwell as his main argument for why he had joined SpaceX and why she should join the company as its vice president of business development. “We will have a hard time spending $100 million in three years.”

While Shotwell was impressed with Musk’s ideas for bringing rocket-part manufacturing in-house, the timing of the offer wasn’t ideal, according to Walter Isaacson’s biography, “Elon Musk.” At the time, she had two young children, was going through a divorce and wasn’t sure she wanted to take a chance on a startup. Eventually, she was sold on SpaceX’s potential to revolutionize the space industry.

“I’ve been a f— idiot,” she told Musk in 2002, according to Isaacson’s book. “I’ll take the job.”

Gwynne Shotwell ‘was the one that was keeping us all of the right mindset and moving forward together.’

— Tim Buzza, former SpaceX vice president

Her immediate tasks were selling customers on SpaceX’s first rocket, Falcon 1, and securing the appropriate permissions to launch at Vandenberg Air Force Base (now Vandenberg Space Force Base) near Lompoc and test rocket engines in McGregor, Texas.

“While we were all working hard on engineering … she was opening up all the doors that were viewed by commercial companies as being some of the most difficult doors to open,” said Tim Buzza, a former SpaceX vice president and the company’s fifth employee, who stayed at the company for almost 12 years.

“All these things, just having a commercial company get onto Vandenberg Air Force Base for our first go-round there ... was really important,” he said. “It gave us some credibility even though we hadn’t done anything yet.”

As Shotwell was piecing together the company’s business strategy, she was also already serving as the glue between Musk and the rest of the team. She helped structure the organization of the company, down to what individual leaders were doing.

“She was the one that was keeping us all of the right mindset and moving forward together,” Buzza said.

That would become important as Falcon 1 rocket development began to sputter. In March 2006, the small rocket lifted off for the first time and cleared the launch pad at the Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands before falling back to Earth and crashing into a reef. The rocket was carrying a satellite built by cadets from the U.S. Air Force Academy.

A second and then third launch attempt ended in similar fashion. All the while, Shotwell was trying to sell customers on SpaceX’s launch capabilities. In discussions with potential customers, Shotwell would highlight the positives: After all, the rocket had cleared the launch pad.

Speaking to reporters after the first launch attempt, Shotwell described the failure as a “setback,” but pledged “we’re in this for the long haul,” according to space news website space.com.

“When these failures were happening, we would just as quickly as we could just ... find the problem, fix the problem and get to another flight, but she was always having to deal with all the other stuff, which is the customers, the press, dealing with financial stuff,” Buzza said. “All of that — that’s probably equally or more difficult than fixing the rocket.”

In 2008, the Falcon 1 rocket finally launched and reached orbit. Armed with that success, Musk and Shotwell went to meet with NASA officials to make their case for a contract to resupply the space station, according to Isaacson’s book.

It was then that Musk asked Shotwell to become president of the company, saying that NASA was concerned he had too much on his plate between SpaceX and his electric car firm, Tesla, and that he needed a partner, according to the book.

SpaceX would go on to win a $1.6-billion contract from NASA to transport cargo to the space station — a deal that saved the company from ruin — followed by contracts to ferry astronauts. In March, the company took a step toward its goal of returning people to the moon — and someday carrying them to Mars — with a largely successful test flight of its massive Starship rocket.

The partnership between SpaceX and NASA wasn’t always easy. The space agency was used to engineering rockets and spacecraft itself, or at least being in charge of the process, and SpaceX often had its own way of doing things.

“This is where her leadership became really obvious — she stepped into some pretty difficult discussions to help the teams see each other’s point of view and then to move forward,” said Michael Suffredini, NASA program manager for the space station from 2005 to 2015, and now chief executive of spaceflight company Axiom Space. “So Gwynne not only led her team, but she really helped evolve NASA’s thinking in these kinds of engineering challenges associated with human spaceflight. And that’s no small feat.”

After an uncrewed SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket exploded on a Florida launchpad in 2016, destroying a customer’s satellite, Shotwell allowed satellite customer SES to embed a U.S. employee in SpaceX’s failure review team to give the company a firsthand look at the problem and the solution. The savvy business strategy worked.

“I don’t know any other organization that would have allowed that,” said Halliwell, the former SES executive. “It was through that relationship, which I think was quite extraordinary, that we managed to get the confidence to continue to use SpaceX.”

Her time at SpaceX, however, hasn’t been without controversy.

The Wall Street Journal reported this month that Shotwell allegedly retaliated against one of her employees after wrongly accusing the employee of having an affair with her husband. Shotwell did not respond to the Journal’s request for comment on the allegation. In the article, which focused on Musk’s behavior toward some female SpaceX workers, employees also criticized Shotwell for defending Musk and not taking harassment allegations seriously.

In a statement to the Journal, Shotwell said SpaceX fully investigates all allegations of harassment and takes appropriate action. She also told the Journal that Musk was “one of the best humans I know.”