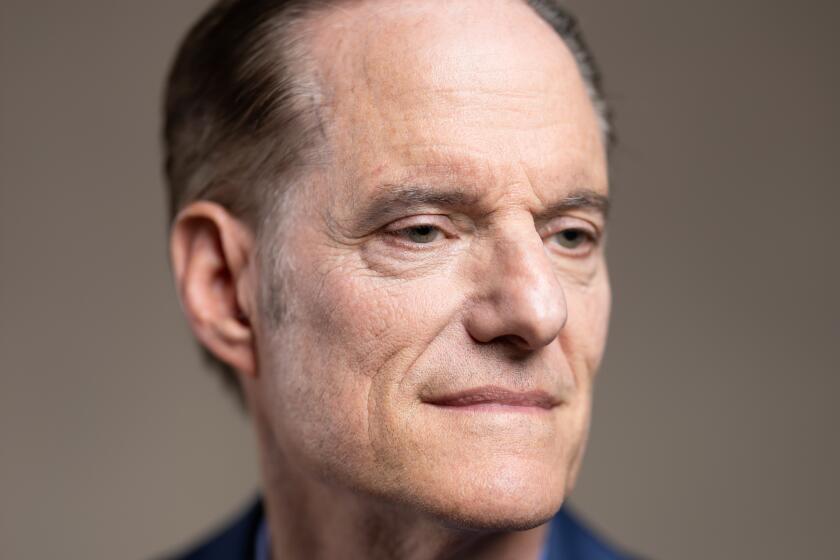

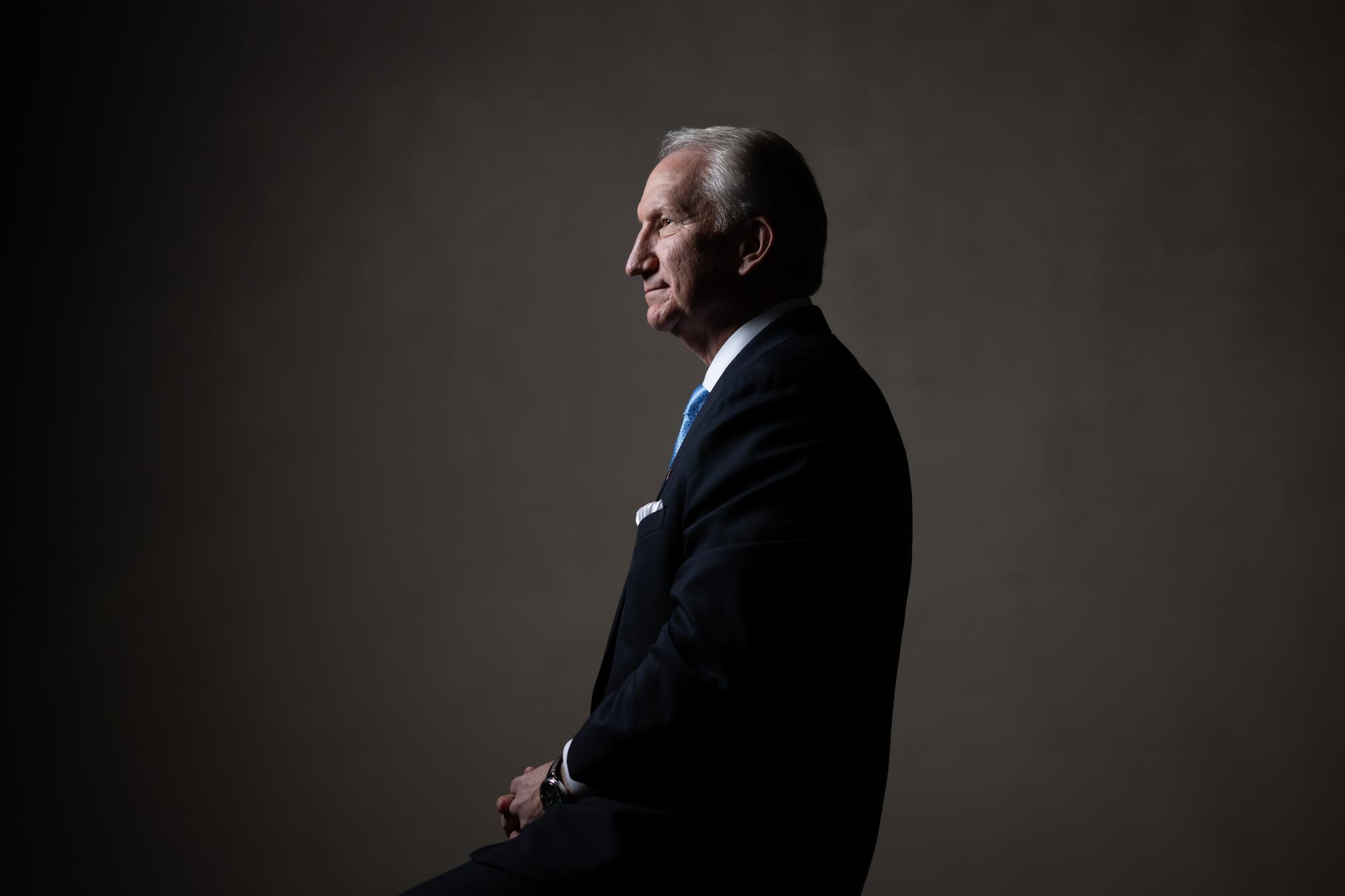

Gene Seroka has been executive director of the Port of Los Angeles since 2014. The seaport moves more cargo containers than any other in the nation. It has handled as many as 10 million containers in a year. Minus holidays, that works out to about 29,000 a day. Any one of them could hold 48,000 bananas or 24,000 tin cans or maybe 12,000 shoe boxes. Part of Seroka’s job is to explain what those numbers mean and why they are important to a Southern California audience consisting mostly of landlubbers.

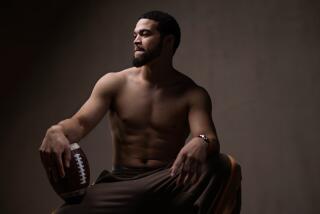

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Disruptors. They include Mattel’s miracle maker, a modern Babe Ruth, a vendor avenger and more. All are agitators looking to rewrite the rules of influence and governance. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

“Every four cargo containers that we move creates one job,” Seroka said. “The more containers we move, the more jobs we create.” Many of those jobs are local. Regionally, an estimated 175,000 Southern California workers — employed at the harbors themselves as well as in related businesses such as trucking and warehouse storage — move freight valued at $469 billion a year, port data show.

COVID-19 put a massive dent in those numbers. During the pandemic shutdowns, Seroka began hosting monthly podcasts with maritime experts, in which he presciently warned about the dangerous confluence of a burgeoning supply-chain mess with overheated consumer demand. “Consumer buying has not let up,” said Seroka, who would become a familiar expert face on CNN, Bloomberg, CNBC and “60 Minutes.” “We are seeing a historic import surge.”

Seroka, 59, met twice with President Biden, ultimately helping forge a solution that helped draw down the dozens of ships anchored outside the port, a logjam that only exacerbated air quality woes at California’s single largest source of pollution.

Longer weekday hours and weekend hours of operation helped. So did Seroka’s decision to fine freight customers for leaving their cargo-filled containers at the port, where they were eating up space. Still, Seroka said emissions remain his biggest challenge: “How are we going to get this port to move from a predominantly fossil-fuel-[dependent industry] to zero-emission, clean manufacturing and clean energy all the way through that supply chain? Quite a task.”

‘How are we going to get this port to move from a predominantly fossil-fuel-[dependent industry] to zero-emission, clean manufacturing and clean energy all the way through that supply chain? Quite a task.’

— Gene Seroka

Seroka lobbies for infrastructure funding in Washington, where he can tell any member of Congress which products coming through the port have been transported to their district. “The cargo that comes through this port reaches every congressional district in the nation,” he said.

Then there is Seroka the salesman, traveling Asia and Europe, flying as much as 400,000 miles a year in his crusade to convince shipping lines that delays are ephemeral and that his port is the most efficient in America and uses North America’s two largest railroad networks to cross the country.

“When it comes to return on investment for the American citizenry,” he said once, “all roads lead to Los Angeles.”