After climbing for the last five years, overall homelessness leveled off in Los Angeles this year, with fewer people living on the streets, according to the annual count released Friday.

The 2024 count, representing a snapshot taken in January, appeared to show the effects of city and county programs to clear out encampments by moving people from tents, makeshift shelters and vehicles into hotels, motels and other forms of temporary housing.

“These shifts in both the city and the county mean that this year, across our region, more people are experiencing homelessness inside, where they are safer, where they have food, showers and better access to medical and other services,” said Paul Rubenstein, deputy chief external relations officer of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, which conducts the count.

LAHSA estimated that there were 75,312 homeless people across the county, including in the city of L.A., down 0.3% compared with the previous year. In the city, the number was 45,252, a reduction of 2.2%, the agency said.

Neither change was enough to be considered statistically significant. But both broke steady upward trends that had seen homelessness grow by more than 40% since 2018.

Reductions in the unsheltered homeless population were more dramatic. The county’s unsheltered population was estimated to be 55,365, down 5.1%. In the city, that number declined by 10.4%, falling to 29,275, according to LAHSA’s figures.

Slow reimbursement of government contracts forces a South Los Angeles home for ex-prisoners to bleed interest to predatory lenders. A small nonprofit proposes to close the payment gap with no-interest loans.

Mayor Karen Bass hailed that progress, saying it shows that city and county leaders have “changed the trajectory” of the region’s homelessness crisis.

“I know that many Angelenos have felt that this situation was hopeless,” she said. “Today we know that we can and we will bring people inside, and move L.A. in a different direction.”

Jennifer Hark Dietz, chief executive officer of the nonprofit homeless services provider known as PATH, called the results an unqualified “win for L.A.” The numbers show that when the city and county put money into the right programs, they can achieve a decrease in the number of “people sleeping outside and a decrease in homelessness in general.”

“It’s definitely not showing us that we can slow down. We have to keep up the pace, and hopefully even increase it. But I do think it gives us all a little bit of hope that we’re headed in the right direction,” she said.

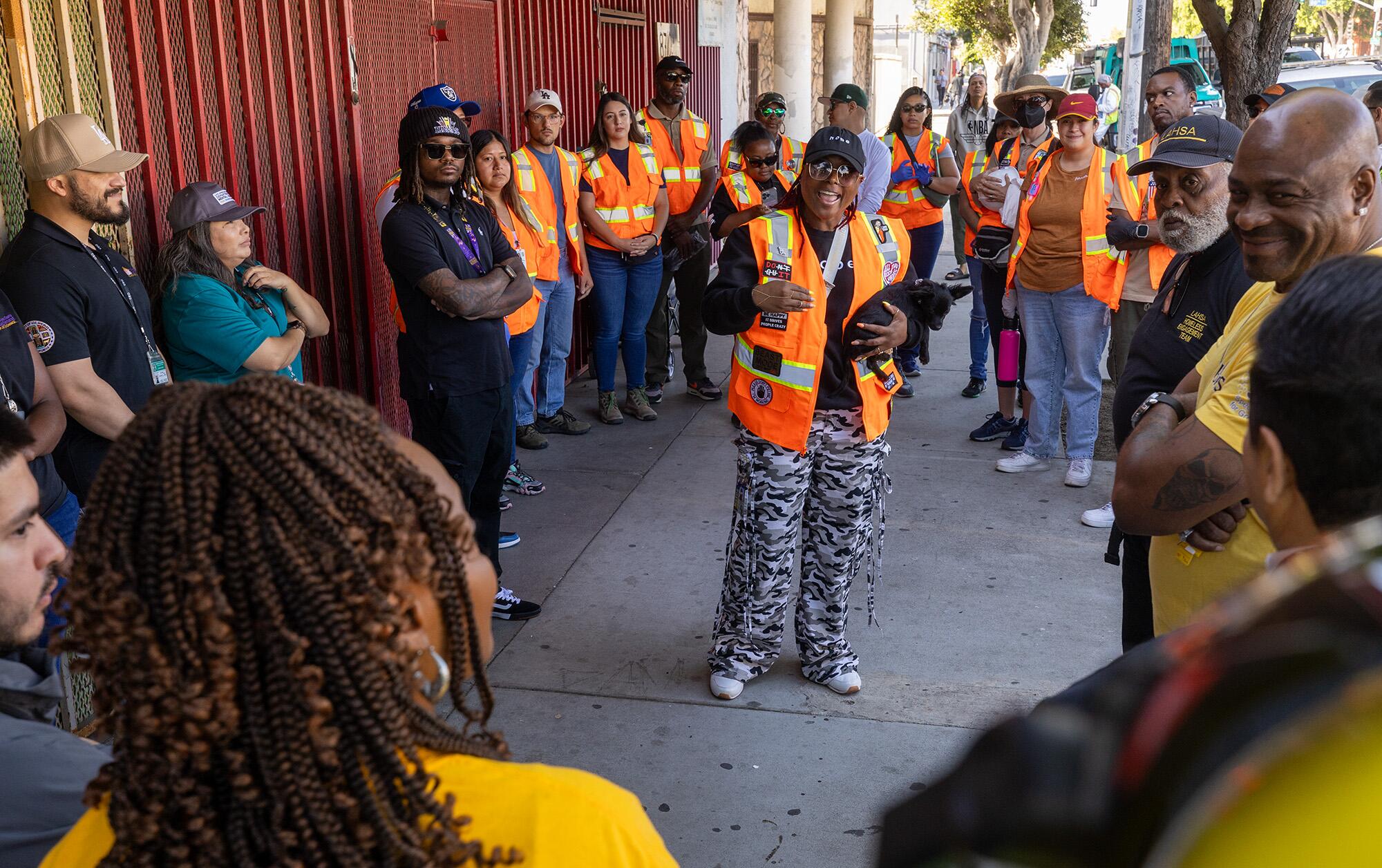

LAHSA officials credited Bass’ Inside Safe initiative — and the close collaboration between city and county agencies — for the decreases in the numbers and percentages of people living on the street.

The count took place shortly after the first year of Inside Safe, which targeted some of the city’s largest and most troublesome encampments. By mid-January, the initiative had gone to 34 encampments at locations stretching from Harbor City near the Port of Los Angeles to Chatsworth in the San Fernando Valley.

At the time of the count, Inside Safe had moved 2,087 people into interim housing. Even accounting for about 400 who returned to homelessness and 329 who were permanently housed, that represented more than half of the city’s increase in its sheltered population.

The county’s corresponding program, Pathway Home, had conducted 10 encampment operations by mid-January, placing 449 people in interim housing.

Inside Safe and Pathway Home have obtained permanent housing for 634 people.

LAHSA’s chief executive officer, Va Lecia Adams Kellum, who created the model for Inside Safe’s clearing of encampments from the Venice boardwalk as head of Venice-based St. Joseph Center, attributed that success to a sharper focus on unsheltered homelessness.

“I want to try to get people inside quickly and safely out of encampments — not a cleanup, not moving people around, not sweeping them from one area to another. I believe that is the most encouraging.”

Under state law, landlords can evict tenants if they are planning a “substantial remodel” of a unit. Long Beach housing advocate Maria Lopez saw it as a loophole in tenant protection law.

Los Angeles City Councilmember Nithya Raman, who heads the council’s housing and homelessness committee, said the new numbers represent a “pretty big turnaround” after years of increases. At the same time, she warned that the city faces “harsh fiscal realities” that will make additional reductions more difficult to achieve.

The city faces serious budget woes. State funding for shelter beds remains at risk, she said, and proceeds from Proposition HHH, which helped finance permanent housing, have been mostly spent.

“I do think that we will be able to continue on this trend this year,” she said. “To continue on this trend over the long term will be more challenging, and will require us to work harder to ensure that we are creating a more efficient system.”

The numbers released Friday showed a distinct shift in populations. As the estimate of unsheltered homeless people declined, the number of those who are sheltered saw major increases.

In the city of Los Angeles, the number of homeless people who are in some form of shelter grew by 17.7%, to 15,977. Across the county, that figure increased by 12.7%, rising to 22,947.

The percentage of homeless people who are sheltered historically has hovered around 25%. In January, it was 35% in the city and 30% in the county, according to the count.

Chronic homelessness, defined as being without a home for a continuous year or at least four times over three years, also declined 6.8% in the county, to just under 30,000.

Another encouraging sign was an increase in the number of housing placements. The county Homeless Initiative reported that 27,300 people had obtained permanent housing, a 24% increase over 2022. The majority of those people came from interim housing, Rubenstein said.

“At this rate, if we could stop anyone else from becoming homeless today, we could end homelessness in just a few years,” he said. “Unfortunately, the root causes of homelessness are as strong as ever.

“To prevent homelessness, the Los Angeles region must reverse decades of underbuilding affordable housing, help more people achieve economic stability and address the shrinking social safety net.”

The numbers were released just days after the county Board of Supervisors cleared the way for a ballot measure that would double the size of the countywide sales tax that raises money for homelessness services — raising it from a quarter-cent to a half-cent. The measure, slated for the Nov. 5 ballot, would also raise money for the production of affordable housing.

Although the numbers provided some glimmers of hope, L.A.’s streets, sidewalks and freeways show that a huge amount of work remains. Right outside City Hall, the corner of 1st and Spring streets — the site of an Inside Safe operation earlier this year — has about 27 tents and other makeshift structures.

On Wednesday, Bass’ Inside Safe program moved about 20 people from the area around Franklin and Argyle avenues in Hollywood. The following day, the area had at least four tents.

Two other groups of homeless people that are estimated separately saw significant decreases. The estimate of 2,406 homeless transition-aged youths was down 16.2% and 2,991 veterans was down 22.9%.

For the second year, LAHSA’s statistical team at the USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work provided a margin of error indicating that the real number for the Los Angeles Continuum of Care — all of the county except Long Beach, Pasadena and Glendale — could be 1,592 more or less than the estimate.

That figure represents the uncertainty in the demographic survey USC conducts after the field count, in which thousands of volunteers walk and drive through almost every census tract in the county and mark down every person they conclude is homeless and every tent, makeshift shelter, car, van and RV.

Based on the survey count of about 4,000, the USC statisticians calculate how many people, on average, live in each of those dwellings. Those factors are multiplied by the count to produce the estimate.

Though the total homeless estimates were too close to last year’s to conclude that homelessness is down, the estimates for the decrease in the unsheltered population were well outside the margin of error.

The Los Angeles results were similar to those of neighboring cities that released their numbers earlier.

For the first time in seven years, the city of Long Beach saw homelessness decline. Long Beach officials said there were 3,376 people experiencing homelessness tallied during the latest count — down 2.1% from 3,447 in 2023.

In Pasadena, the number was unchanged at 556.

In contrast, Orange County recorded 7,322 homeless people, up 28% from 2022.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.