Second earthquake in two days rattles Los Angeles, striking in El Sereno

A magnitude 3.0 earthquake struck the eastern Los Angeles area Tuesday afternoon, two days after a magnitude 3.4 temblor hit nearby.

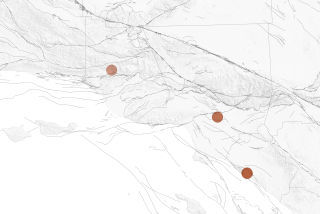

The latest quake struck at 3:05 p.m., with an epicenter about a block north of El Sereno Elementary School, in the Los Angeles neighborhood of El Sereno, beneath Elephant Hill Open Space. That’s two miles southwest of downtown South Pasadena and two miles northwest of Cal State L.A.

Weak shaking was felt in East Los Angeles, Alhambra, Monterey Park, Vernon, Maywood, Commerce and Bell, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

The earthquake’s epicenter is less than two miles south of the Raymond fault, which runs from northeast L.A. through South Pasadena, Pasadena, San Marino, Arcadia, Monrovia and the unincorporated area of East Pasadena. For stretches, the fault runs alongside parts of Eagle Rock, York and Huntington boulevards and under a stretch of the 110 Freeway in South Pasadena.

The Raymond fault caused the magnitude 4.9 Pasadena earthquake in 1988, one that literally threw seismologist Lucy Jones out of bed.

Sunday’s magnitude 3.4 earthquake, also in El Sereno, was centered three-fifths of a mile to the south of Tuesday’s quake. Its epicenter was two blocks south of the intersection of Huntington Drive and Eastern Avenue.

Earthquakes are a way of life if you live in Los Angeles. But what about when you never feel them — even as your Shake Alert is blaring and your friends are buzzing about the temblor?

Weak shaking from Sunday’s quake may have been felt more broadly, including in downtown L.A., Burbank, Pasadena, El Monte, Montebello, Pico Rivera, Downey, Lynwood and South L.A.

Seismologists have looked with concern at the Raymond fault. It’s possible it could rupture nearly simultaneously with a couple of faults to the west — the Hollywood and Santa Monica faults.

The Hollywood fault runs through some of the most densely populated parts of Los Angeles.

Evidence for the Raymond fault has been clear to geologists for decades. A lake that once sat at what is now Lacy Park in San Marino was created by the fault, the result of land sinking from past earthquakes.

Those historic quakes also created the hills that are now part of the Los Angeles County Arboretum & Botanic Garden in Arcadia, as well as those that give the commanding views at the Huntington Library, home to an estate, library, art collection and gardens established by railway magnate Henry Huntington.

Compared with the fastest-moving faults in the state, the Raymond moves slowly — at about one-tenth the speed of the infamous San Andreas fault. That means the Raymond doesn’t rupture as often as the San Andreas.

Scientists suspect the last time the Raymond fault produced an earthquake of magnitude 6 or above was 1,000 to 2,000 years ago. They believe such events happen every few thousand years, on average.

But earthquakes don’t happen like clockwork, and scientists cannot say for certain when the Raymond fault will rupture next.

An average of five earthquakes with magnitudes between 3.0 and 4.0 occur per year in the Greater Los Angeles area, according to a recent three-year data sample.

Did you feel this earthquake? Consider reporting what you felt to the USGS.

Are you ready for when the Big One hits? Get ready for the next big earthquake by signing up for our Unshaken newsletter, which breaks down emergency preparedness into bite-size steps over six weeks. Learn more about earthquake kits, which apps you need, Lucy Jones’ most important advice and more at latimes.com/Unshaken.

An earlier version of this story was automatically generated by Quakebot, a computer application that monitors the latest earthquakes detected by the USGS. A Times editor reviewed the post before it was published. If you’re interested in learning more about the system, visit our list of frequently asked questions.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.