Anyone who caught even a passing glance of a USC football game the last two seasons should know how much Caleb Williams meant to a program that had spent the better part of the previous decade in a dark place. The quarterback’s decision in the spring of 2022 to follow his coach, Lincoln Riley, from Oklahoma to USC, changed the trajectory of Trojan history, as USC pivoted from a 4-8 team to one that won 11 of his first 12 games and became a College Football Playoff contender and, once again, a national story. That December, Williams became the eighth Trojan to win the Heisman Trophy. Of those eight, who include Mike Garrett, O.J. Simpson and Carson Palmer, Williams may be the most talented.

Discover the changemakers who are shaping every cultural corner of Los Angeles. This week we bring you The Disruptors. They include Mattel’s miracle maker, a modern Babe Ruth, a vendor avenger and more. All are agitators looking to rewrite the rules of influence and governance. Come back each Sunday for another installment.

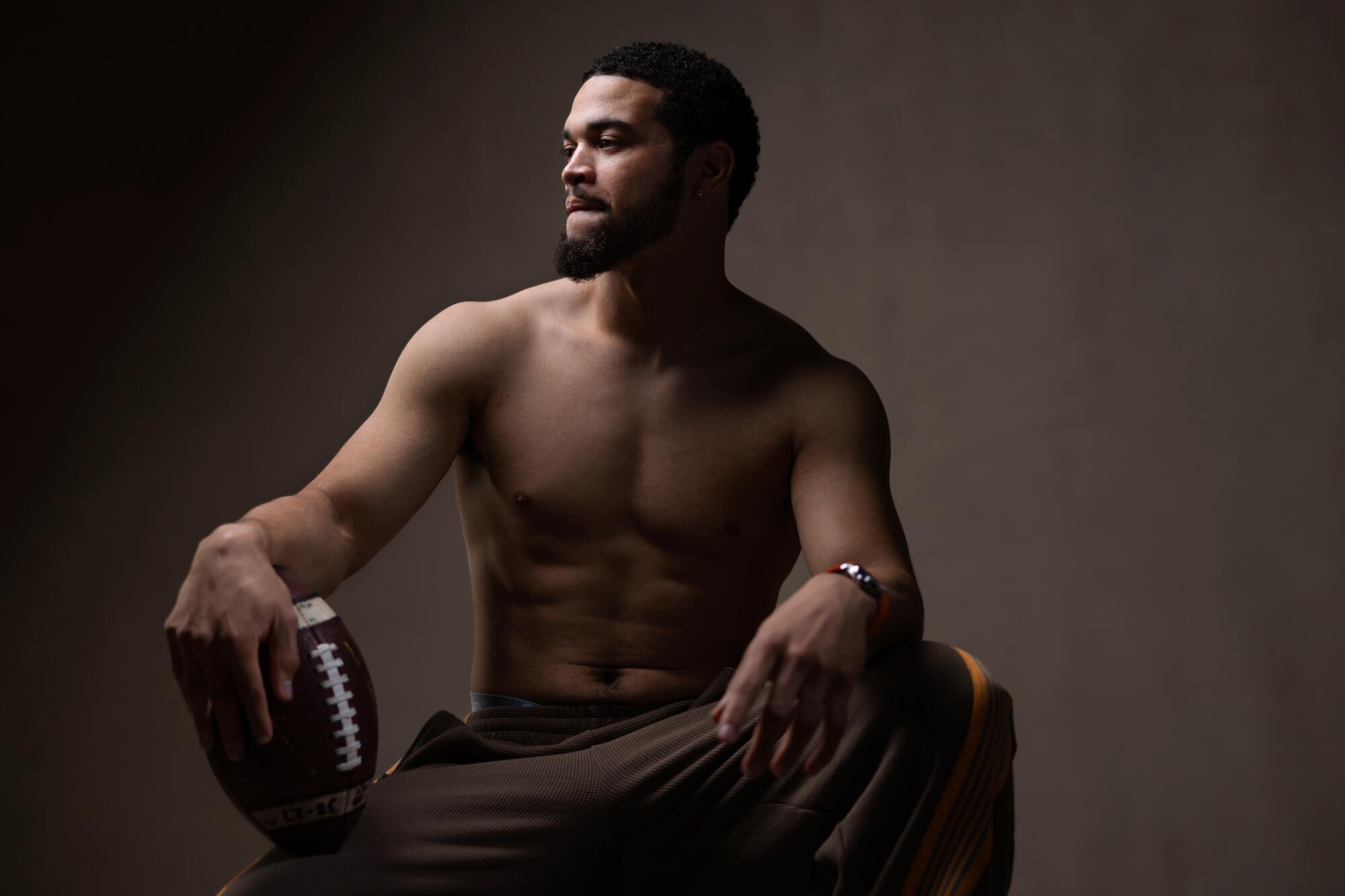

Football field magic alone did not make Williams, 22, an overnight sensation in the Southland. Williams is not merely a generational talent, but also a face, maybe The Face, of his generation’s disruption of a college sports economic model in which athletes, no longer nominal amateurs, can now cash in on their name, image and likeness. While at USC, Williams built an NIL portfolio worth a reported $10 million that includes such massive brands as Wendy’s, Dr. Pepper, Nissan, Beats, Postmates, Neutrogena and ALO Yoga.

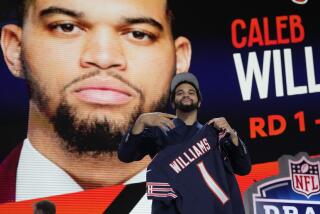

The wins came less easily last season — USC finished 7-5, losing five of its last six — and the criticism has flowed more freely, and sometimes more pettily. But in a city built around The Brand, among individual athletes, only LeBron James’ imprimatur has carried greater weight in the last year. Williams’ influence is only growing: At the NFL draft in April, the Chicago Bears selected him as the No. 1 overall pick.

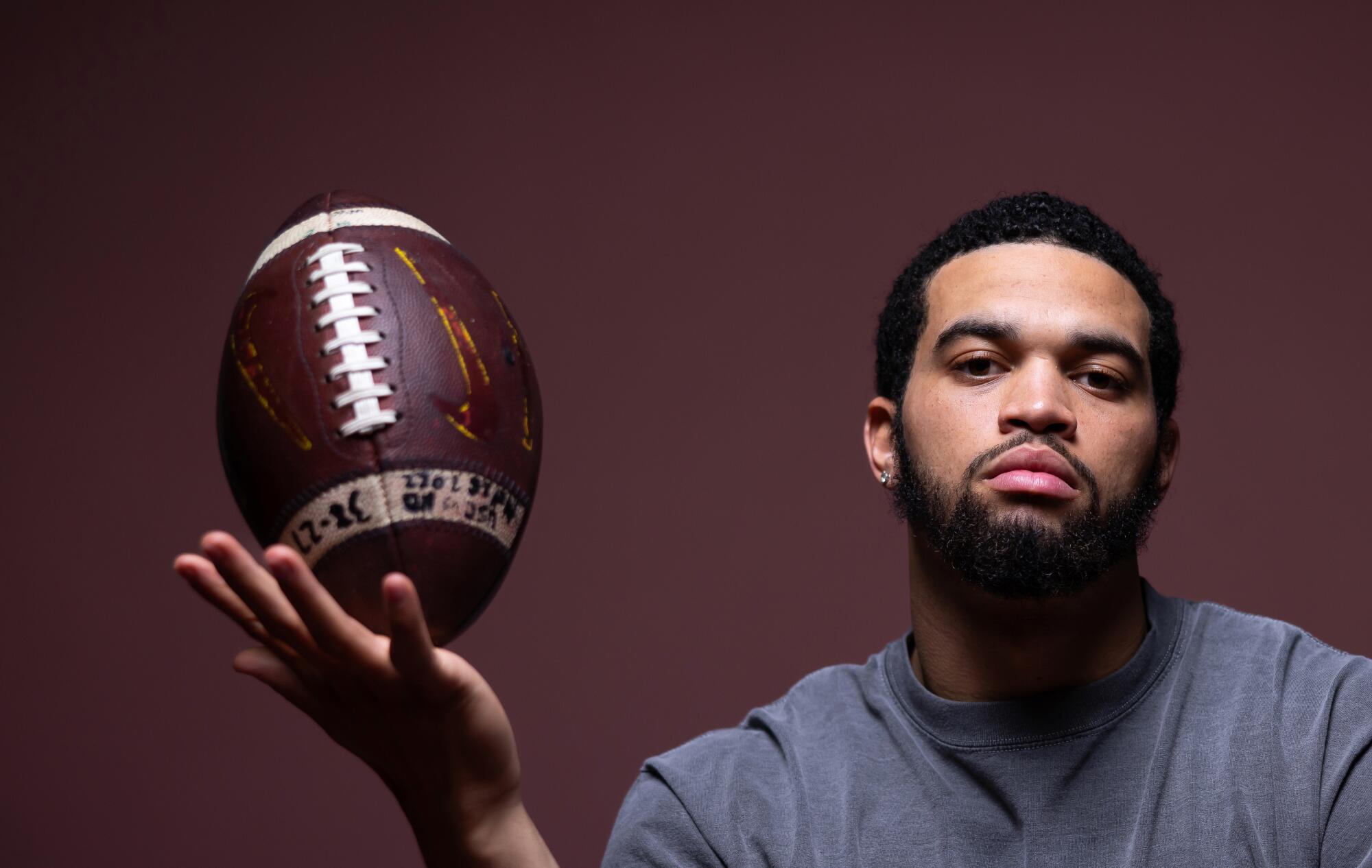

But Williams has spent a while now in the spotlight and grown comfortable with pressure bearing down around him. Two years ago, before the Heisman Trophy or the Dr. Pepper commercials or the swirling speculation about his future or his fingernails or his tears, Williams kicked back in the bleachers of the L.A. Coliseum, looking out over the empty stadium and the sprawling city where he’d soon become a national icon.

Already, Williams had some grasp of his place in the changing landscape of both his new city and college sports more broadly. He recalled a lesson his father, Carl, taught him years earlier, one that would come in handy later when everyone and their brother tried to quantify his worth.

“Always come in with my number,” Williams said. “And if they don’t want it, well — you know your own value.”